Street hydros captured the imagination of Seattle youth

Aug 3, 2023, 8:06 AM | Updated: 9:52 am

A famous local hydroplane driver calls it a “universal tribal ritual” that flourished for about 25 years, all because of the annual Seafair races.

If you’re a male between the ages of roughly 45 and 65 who grew up around Seattle, this story will make complete sense to you.

If not, well, set aside your disbelief and grab a Schwinn Stingray, some twine, and a flat piece of wood about the size of a laptop computer and pedal back about 50 years to a much simpler time.

From early July to early August, from roughly the mid-1950s to the late 1970s, little boys (and, as we’ve since heard from a lot of KIRO listeners, a fair number of girls, too) in neighborhoods in and around Seattle made crude miniature wooden hydroplanes and pulled them behind their bicycles in driveways and on city streets. Some kids raced against each other, some just pulled their boats up and down the street for show, and some made jumps out of curbs and other features along the sidewalk.

RELATED: Hydroplanes echo through Seattle history

How did it work, exactly?

Writer, television performer and former Almost LIVE! frontman John Keister explains it this way.

“In my neighborhood, which was close to the actual hydroplane pits, I lived kind of near Seward Park, on every block the boys would tie little wood carved hydroplanes behind their bicycles,” Keister said. “And we would have these hydroplane races out in front of the houses on the blocks that we lived in, and would paint them our favorite hydroplane of the moment.”

Keister says that he and his friends had elaborate “heats” just like the real races, and used things like manhole covers as “turn buoys” and chalk to mark the start and finish lines.

Keister’s earliest favorite hydroplane was the Miss Thriftway, aka “The Grocery Wagon,” which he pulled behind his Schwinn Stingray, complete with butterfly handlebars and a banana seat.

In the early years, Keister says the simple design of the boats meant a lot of “accidents” as the tiny hydros often flipped over when negotiating turns, not unlike the real boats back then, too.

But Seward Park, Keister says, was something of a hothouse for street hydro design and innovation when he was a kid.

“Somebody got the idea of nailing on sponsons like the actual boats had, which was the real three-point design over the water,” Keister said. “And when the first kid did that, we suddenly realized that, ‘Wait they don’t flip over if you do that.’ So we all hammered our own wood-fashioned sponsons on the boats, and they rode much better.

“We adopted the design of the real boats,” Keister said, just like those racing on Lake Washington a few blocks away. “I believe my cohort, at least in my neighborhood, was the first to do that.”

In the late 1960s, a few miles north of where John Keister grew up, future musician and Presidents of the United States of America guitarist Dave Dederer was tearing up the sidewalks and cul-de-sacs of Laurelhurst in his gold-painted hydro, pulled behind his B-list Murray bike, also with fancy handlebars and a banana seat.

“It was just a very joyous feeling to have that thing on that 20 or 30 foot piece of string or rope behind your bike and you would go around corners like sort of learning to control how it would swing out behind your bike, you know like pulling a water skier or somebody on an inner tube,” Dederer said.

“There’s something inherently satisfying about that,” he said.

And just like a windy day on Lake Washington, the streets offered up their own kinds of mini-hydro danger.

“A lot of northeast Seattle had segmented pavement, or a lot of Seattle, in general, had segmented pavement and if you had [a hydro] that was crappy or that wasn’t big enough or heavy enough or didn’t have good bevels, every time you hit a bigger segment it would flip over and ruin your fun,” Dederer said.

Unlike Keister and his friends in Seward Park, Dederer’s gang didn’t compete against each other.

“We never raced,” Dederer said. “I don’t ever remember it being about a race. It was more like an expressive thing, you know. It was a way to express yourself.”

One way they expressed themselves was through acrobatics.

“In Laurelhurst at that time, all the streets had sidewalks,” Dederer said. “And some of the curbs were hard curbs, and some were those rounded convex curbs, and they made these perfect little jumps. So we would tow our boats to places that had good driveway curbs and then you’d go shoot up those on your bike and then the hydro would jump off them behind you.

“It had danger. It had emotion. It had speed. It [made] a good sound, too,” Dederer said. “I remember vividly on that rough segmented pavement that it made a very specific sound, that “HRRRRRR” [of] plywood rattling along on there.”

Dederer didn’t name his boat after one of the real ones, but he does recall a particularly sweet gold-painted finish on his miniature plywood boat one year.

RELATED: Did archaeological group solve the ‘Beeswax Ship’ mystery?

Over on Rose Hill in Kirkland in the early 1970s, Q13 anchor Bill Wixey was pulling his very own miniature Miss Pay n’ Pak (named in honor of the late, great, local home improvement chain).

“I just remember tying a rope to the back of my bike, and I can’t remember the kind of bike, but I do remember I had playing cards in the spokes to make it even more intimidating to the other competitors,” Wixey said. “And it was intimidating.

“I don’t remember if I actually bothered to paint the thing,” he continued. “But you know, after about a week or two of doing these silly races with my friends as we drive [our bikes] around a cul-de-sac or whatever, those pieces of wood were chipped up pieces of twig at that point.

“But we didn’t care,” Wixey said. “It was still a ton of fun.”

Legendary real hydroplane driver Chip Hanauer grew up in Bellevue’s Newport Hills neighborhood in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Before he ever raced a real boat (which he started doing at age 10), Hanauer cut his racing teeth on bike-pulled street hydros.

At first, Hanauer says, his was a thing of beauty.

“My father was a really good woodworker, that was his avocation,” Hanauer said. “He made this really gorgeous, beautiful thing that was all to scale and looked like a hydroplane.

“I took it [out on the street] and it was terrible because all these other guys had this flat piece of plywood that was real wide and looked like hell and had a tail stuck on it. But it stayed right side up. Mine looked really good but it kept flipping over on its side.

“So I ended up abandoning my father’s beautiful work of art and just getting a piece of plywood like everybody else,” Hanauer said.

Did Chip Hanauer decorate his plywood hydro to match one of the real ones?

No, Hanauer says, his little boat should’ve been called the “Miss Plywood.”

“It was just a sheet of plywood,” Hanauer said. “And actually the perfect hydroplane to tow behind your bike was just a piece of plywood. The minute you tried to make it look more like a hydroplane the worse it worked. So if somebody just went to Home Depot and got a complete big sheet of plywood and could pull it, that would actually be the ideal vehicle.”

Even with the Miss Plywood, Hanauer was a serious competitor, studying every aspect of the “boat,” including the “propulsion system” – the string that connected the motive power of the bicycle to the tiny slab of wood being dragged down the road.

“Nothing was worse than the string breaking, and that was humiliating,” Hanauer said. “So I went and got twine, this really, really strong twine because some guys were using the string they got out of the kitchen that their mothers used on the turkey, and that obviously didn’t work worth a damn.

“I think if I could’ve found [steel] cable I would’ve used that, but the best I could find was twine,” Hanauer said.

And during that later storied career driving the likes of the full-sized Atlas Van Lines and Miss Budweiser, did anything Hanauer learn on the streets of Newport Hills come in handy on the lake or the river?

“Yeah,” Hanauer said. “Cut people off as much as you could. Push them over if you could get away with it. All that kind of stuff.”

It’s Hanauer who called street hydros a “universal tribal ritual that died away but was amazingly strong during that period of time.”

And Hanauer marvels at the fact that it was a “sport” that was never commercialized or formalized in any way; there were no kits you could buy to build a boat, no leagues to join or organized races to register for. It was all homegrown and organic.

Also, Hanauer says, it was an activity that was unique to Seattle.

“Kids didn’t do this in Detroit, or even in the Tri-Cities,” Hanauer said.

So, where did the notion for street hydros come from, exactly?

RELATED: The first and nearly forgotten Independence Day celebration

No one knows for sure. But a significant moment in local history was when the famous Seattle boat Slo-Mo-Shun IV won the Gold Cup, known as the “Kentucky Derby of boat racing,” in Detroit in 1950. This meant the Gold Cup Race came to Seattle in 1951, which was the equivalent of hosting the Super Bowl. Slo-Mo IV also broke the speed record during a timed run on Lake Washington, which was a huge deal in Seattle and all around the world

Keister puts it this way.

“You have to understand, [for] a city that was pretty remote and didn’t have any other professional sports teams, how dearly the one thing that you were really good at, at building hydroplanes, the one thing that the city really excelled at, became very important to a city that, in many ways, was just a big town, [back] in the day,” Keister said.

“[Hydroplanes] also really resonated really differently in different neighborhoods. There was definitely a Norwegian-Scandinavian boat, which was Bardahl. There was a definite Catholic boat in the race, I’m being completely serious, the Notre Dame. And then there were the Slo-Mo-Shun boats, which was just the crazy designers, the guys at Boeing who did crazy things, you know.

“It was important to the town at that time,” Keister said.

Legendary DJ, impresario and Emeritus Voice of Seafair Pat O’Day passed away in August 2020. When KIRO Newsradio spoke to him for this story in 2018, he concurred with Keister.

“Seattle didn’t have major league anything [in the 1950s],” O’Day said. “The Huskies never went to a Rose Bowl and the Seattle Rainiers were the only teams of any sort. And so the hydroplanes just dominated the feelings and the imagination of the youngsters of the community.

“And how would you participate in such a thing? You can participate in touch football and baseball, but hydroplaning? Well, they built their little models because they were so crazy about the sport and what it was doing, and how do you make it go, you put ’em behind the bicycle and you pull ’em,” he said.

“That’s how it all came about,” O’Day said.

It’s unclear when the street hydro phenomenon died out, but the best guess is that it mostly went away by sometime in the late 1970s, perhaps after the Mariners were founded and chased away any notion that Seattle wasn’t a big league city.

Meanwhile, Hanauer, still something of a feisty competitor, bristles at a question about whether he ever bothered to paint his street hydro, the way Bill Wixey, Dave Dederer or John Keister did.

“No! I’m telling you, a flat piece of plywood was the way to go,” Hanauer said.

“No adornment, no nothing. Just a flat piece of plywood. If I would’ve been smart enough then, probably a flat piece of steel would’ve been better. I would’ve used that.

“I’d like to see Keister deal with me and my flat piece of steel,” Hanauer said, chuckling.

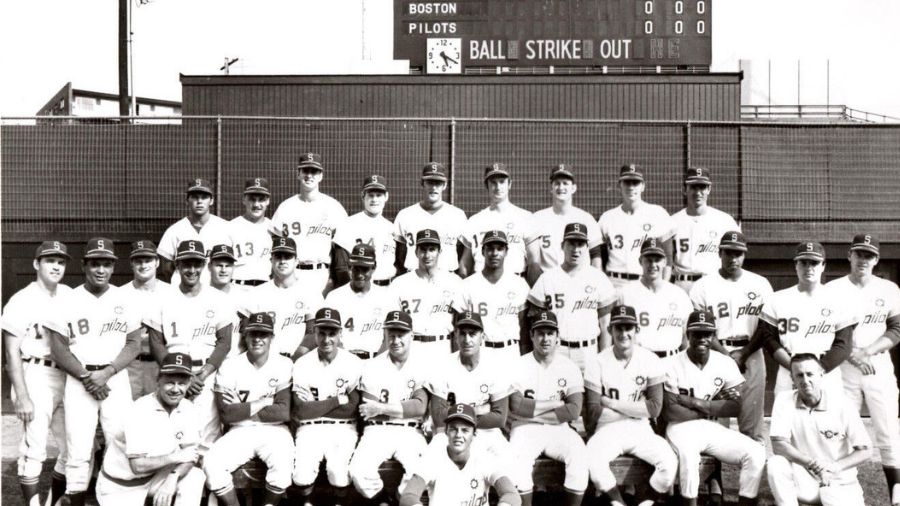

Very little exists in the way of photographic “evidence” of the street hydro phenomenon. Do you still have the miniature wooden “street hydro” you pulled behind your bike or do you have photos? If so, please send new or vintage photos via email to fbanel@kiroradio.com.

You can hear Feliks every Wednesday and Friday morning on Seattle’s Morning News with Dave Ross and Colleen O’Brien, read more from him here, and subscribe to The Resident Historian Podcast here. If you have a story idea, please email Feliks here.

![Chad Bystrom writes, "My grandfather and I made [this] together. I used to pull this thing around Mason Lake when I was a little kid" and Chad would occasionally take it out on the streets, too. (Chad Bystrom)](https://mynorthwest.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Lego-hydro-from-Chad-Bystrom-150x150.jpg)