All Over The Map: Cascade Mountains named for a ‘terror to navigation’

May 10, 2019, 10:59 AM | Updated: 11:51 am

Lewis and Clark referred to them as the “Western Mountains.”

Boston-based Oregon Country enthusiast Hall J. Kelley wanted to rename the individual peaks for commanders-in-chief and call the whole thing “The Presidents Range.”

But the name that really stuck on the Cascade Mountains came from a navigation hazard that disappeared beneath the waves 80 years ago.

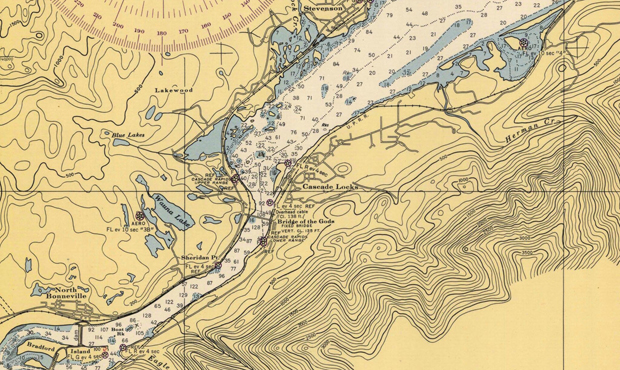

That hazard was called “the Cascades of the Columbia,” a name that likely dates to sometime after the arrival of the fur traders who founded Astoria in 1811. The rapids were about 140 miles upriver from the Pacific Ocean, in the area where the river cuts through the middle of the mountain range that we now know as the Cascades.

The Cascades of the Columbia stretched over a distance of just under six miles. A 1926 history of the Columbia that calls the Cascades a “terror to navigation,” also says that the river level dropped a total of 37 feet over that distance, with a 21-foot drop in the main rapid taking place over less than half a mile.

A massive rock collapse known by geologists as the Bonneville Slide gets the blame for creating the Cascades. Scientists are uncertain of the date, but it could have happened as recently as 400 years ago, or nearly a thousand years ago. Other theories posit that there may have been a series of slides over several hundred years.

When the rocks slid – and some were as large as 800 feet long and 200 feet wide – the Columbia was blocked by a natural dam estimated to be 200 feet high and 3.5 miles long. The massive lake that formed behind the dam stretched upriver for 70 miles until the dam eventually burst and washed much of the material down river. The “Bridge of the Gods” legend, for which a nearby highway bridge is named, likely has its origins in these geologic events.

Scottish botanist David Douglas, for whom the Douglas Fir is named, and who roamed around here observing, sketching, and note-taking almost 200 years ago, gets credit for first using the phrase “Cascade Mountains” and “Cascade range of mountains” in his journals in the 1820s. He never claimed that the name was his idea, though. Douglas died in Hawaii in 1834 at age 35 under mysterious circumstances.

Either way, the Cascades were a pretty serious obstacle to the fur traders who wanted to travel up and down the Columbia, and to Oregon Trail travelers, some of whom (including Seattle’s Denny Party) made the last part of the journey west by ditching their wagons at the Dalles, and floating down the Columbia to the Willamette River and then on to Portland or Oregon City.

In the early years, anyone traveling on the Columbia had to “portage” around the Cascades — that is, get out of the river, and travel around the Cascades on foot. In 1851, a portage railroad was built, considered the first railroad anywhere in what’s now Washington.

It was pretty crude. It was donkey-powered and used wood rails covered in cowhide, but it was a marked improvement over walking and dragging all your worldly goods along the river bank.

The portage railroad was improved over the years, but ultimately a new solution was required to handle larger vessels and expanding traffic on the river. So, in 1896, the Army Corps of Engineers built the Cascade Locks, which bypassed the worst of the rapids, and allowed steamboats to go back and forth safely between Portland and the Dalles (though a few brave captains actually made it through the Cascades in the years before the locks).

In 1938, the Bonneville Dam was completed downriver from the Cascades and the Cascade Locks. Like the rock slide, the dam is named for French-born Captain Benjamin Bonneville of the U.S. Army, who is also namesake for the company that owns KIRO Radio.

As early as 1932, river water began pooling behind the dam, eventually eliminating the Cascades and also making the Cascade Locks obsolete.

A similar obstacle several miles upriver called Celilo Falls was legendary as a fishing spot, and as crossroads of culture and trading activities for Native Americans for millennia. Celilo Falls also had a bypass canal dug around it 1915. That canal was made obsolete and the entire falls disappeared – and an entire culture was disrupted – when the Dalles Dam was completed in 1957.

Visiting the sites of the Cascades and of Celilo Falls in 2019, it’s possible to imagine how both places looked before they were altered, mainly thanks to photos and written descriptions. What’s impossible to imagine — and to fully appreciate the loss of — are the sounds, smells and Native culture of the Columbia that also went away along with the navigation hazards.

More from Feliks Banel