Fight for quiet in Olympic National Park pits Navy versus nature

Oct 9, 2019, 6:21 AM | Updated: Oct 11, 2019, 9:36 am

What do the Navy’s unique Growler jets have to do with one man’s mission to save silence?

Island residents grumbling over Navy’s Growler jet noise

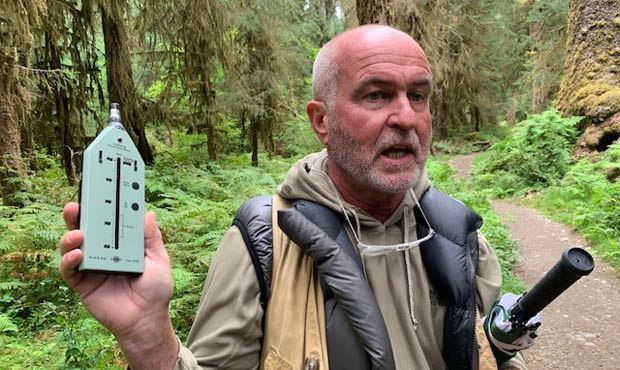

A self-described “sound tracker,” acoustic ecologist Gordon Hempton claims fewer than 10 places in the U.S. remain free of noise pollution. He considers true quiet not an absence of sound, but the complete removal of human-caused noise.

“Silence is so important to me, because without silence I don’t think I’d even know who I was,” said Hempton on a recent afternoon in Washington’s Olympic National Forest, a place he considered one of the least noise-polluted in the country… until recently.

As an award-winning acoustic ecologist, Hempton travels the world to record nature’s soundtrack. His audio portfolio includes snow melting, the Ecuadorian Amazon, and Haleakala Crater on Maui – dubbed “The Quietest Place on Earth” – where the sound pressure level is negative decibels inside the crater.

Hempton’s recordings span nearly four decades. After all those years, he’s declared one of the quietest spots in the lower 48. Established on Earth Day 2005, he calls it “One Square Inch of Silence.”

“This simple one square inch will be defended from all sources of noise pollution,” Hempton said, standing in front of the “gateway” to one square inch.

It’s located in Olympic National Park’s Hoh Rain Forest, where annual rainfall totals average 12 to 14 feet. Thick layers of moss cover nearly every tree and the “air is absolutely still and moist.” Hempton claims it’s even possible to hear a hemlock seed fall 300 feet to the forest floor.

Enter the Growler

In recent years, air travel has increased over the park, drowning out some of its natural sounds. That includes an average 2,300 training flights a year by Boeing-made EA-18G Growlers, fighter jets built for electronic warfare. It takes them only about ten minutes to fly past the rain forest from Naval Air Station Whidbey Island, approximately 75 miles away.

“We have a unique mission. We’re the only one that does it in the world,” said Commander David Harris, Commanding Officer for the Electronic Attack Squadron at NAS Whidbey, the Navy’s only Growler training team.

The stealthy planes contain electronic jammers that are used to scramble, confuse, and shut down enemy signals. They train in the Olympic Military Operations Areas, airspace established by the Federal Aviation Administration in 1977.

It stretches across a section of the Olympic Peninsula and extends into the Pacific Ocean. The growlers arrived in 2008, and now more are likely on the way after the Navy approved an expansion of the fleet.

“We are very much in demand because, not only the Navy, but all of our coalition and ally partners want the Growler there whenever possible, because we provide them this umbrella of protection,” said Harris. “We’re very, very busy and we could definitely use some help in getting more assets on board.”

The Navy’s plans include an additional 36 growlers, bringing the total to 118. Military officials estimate that will increase the number of flights over Olympic National Park to 2,600.

The Growler expansion has been scrutinized by Washington Attorney General Bob Ferguson, who alleges the Navy’s environmental impact statement did not thoroughly examine the planes’ effects on people and wildlife. Ferguson has filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court in Seattle, challenging the environmental review.

Dori: Ferguson suing Navy over Growler noise just grandstanding

While the Navy acknowledges the sound impact over Olympic National Park, officials said the FAA controls where the growlers can train. The National Parks Conversation Association argues they could voluntarily fly elsewhere.

The association has launched a campaign, called “Hear Our Olympics.” It calls for the Navy to leave the national park’s skies, suggesting they train at other airbases and military airspace.

One example, according to the association, is Mountain Home Air Force Base in Southern Idaho, where the Navy conducts similar training. NAS Whidbey officials estimate that would cost an extra $5 million a year and worry it would waste valuable training time. Harris estimated flying to the Idaho base would take up to an hour.

“There’s another huge cost that’s factored in and that’s the wear and tear on the aircraft,” said John Mosher, the Navy’s U.S. Pacific Fleet Northwest Environmental Program Manager. “Putting additional mileage on them just to get to and from another airspace decreases the service life.”

Mosher said they try to minimize the Growlers’ disturbance by flying high and using more flight simulators. Gordon Hempton said he appreciates the Navy’s effort but thinks it’s not enough to ensure his “One Square Inch of Silence” remains silent.

“They’re no enemies of quiet. They’re just people trying to do their job, and they just need their job redefined a little bit,” said Hempton. “Our national parks belong on earth and in the sky for everybody to enjoy.”

For now, the skies above the Olympic Peninsula belong to the Navy’s mission of defending freedom. What that sounds like is up for debate.