How King County’s first state representative disappeared in mysterious shipwreck

Oct 9, 2019, 7:27 AM

The best Pacific Northwest shipwreck stories have at least one thing in common: An element of mystery, or some unanswered question that lingers, eons after a particular vessel was last seen disappearing over the western horizon, or under the choppy waves of the Pacific.

Searching for lost clues about the winter of 1861-1862

And shipwreck stories used to be something of a social commodity around here, when our region’s maritime links were more numerous, more robust, and more concrete. Nowadays, with our economy so much more “virtual” or land-based, our maritime history can feel so theoretical, abstract, and distant.

That’s why a shipwreck from 125 years ago this week is worth remembering, and worth talking about at the kitchen tables, on the front porches, and even along the piers of Puget Sound.

The story starts not at the beginning, but on a characteristically windy day at the Southwest Washington coast. It’s one week before Christmas 1894. It’s a Tuesday, and a woman is walking on the beach, when she makes a mystifying discovery.

Who is the woman, and why is she walking on a remote stretch of beach in late December?

We don’t know her name, but we know that she’s married to one of the lighthouse keepers at Willapa Bay. Based on the archives available, that means her husband could be Marinus Stream, Rasmus Petersen, or Anders Gjertsen.

The lighthouse at Willapa Bay was first erected in 1858, when that body of water was known as Shoalwater Bay. A constant beacon was a fixture on the north spit of the bay from 1858 until 1940, when beach erosion meant the 80-year-old navigational aid had to be abandoned for good.

What the lighthouse keeper’s wife found on her blustery walk that long-ago day was a long wood plank, sticking straight up from the sand. A closer inspection revealed that a large letter “E” was visible on one side, and it had obviously been hand-painted on the board by a talented commercial artist. Once the plank was plucked from sand, it became clear that the “E” was the final letter in a name. That name, revealed as the sand fell or was brushed from the plank, was “IVANHOE.”

The IVANHOE

It was a “name-board” that came from a ship that had been missing for more than two months. But, because of an earlier discovery in British Columbia, it was a surprise to find anything from the IVANHOE this far south.

IVANHOE was a sailing ship that left Seattle sometime between September 27 and September 30, 1894. Specific departure dates vary by a day or two among the many sources, including newspaper accounts at the time and maritime history books written not long after, but all sources agree that the ship was loaded with coal for the California-based Black Diamond Coal Company, and that ship and cargo were both headed to San Francisco.

On the day the ship left Seattle, the tug TYEE towed IVANHOE out of the Strait of Juan de Fuca and into the Pacific Ocean. Another Black Diamond Coal Company-owned ship, the YOSEMITE, was nearby and was also headed for San Francisco. An unrelated ship, the ROBERT SUTTON, was in visual contact with IVANHOE for several hours the next day, up until the time when a storm blew in from the southeast, and clouds and rain obscured the SUTTON’s view.

According to Lewis & Dryden’s Marine History of the Pacific Northwest, originally published in 1895:

The IVANHOE was built at Belfast, Maine, in 1865, and was 202 feet long, 39 feet beam, and 27 feet depth of hold, net tonnage 1,563. She had been in the coasting trade between San Francisco and Northern coal ports for several years and was owned by the Black Diamond Coal Company.

For that fateful voyage in 1894, a crew of 20 was aboard, led by Captain Edward D. Griffin and mates James J. Tohogg and Charles Christiansen (spellings vary for the names of both mates). Also aboard IVANHOE were five passengers: A stowaway from Sacramento named Edward Aliardyce (it’s unclear how his name, hometown. and stowaway status were known to newspaper writers after the wreck); Allen B. Fogler; Mrs. Mattie L. Bara; Mrs. Dr. Irene Molen; and a journalist, historian and former elected official named Frederic James Grant.

King County’s first state representative

Frederic J. Grant is the most interesting of the five passengers, though the stowaway is certainly a close second.

Grant was barely 32 years old when he stepped from a Seattle pier and onto the deck of the IVANHOE. He was born in Ohio on August 17, 1862, and graduated from Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania in 1883.

By 1889, Grant was elected to the first Washington State House of Representatives, representing King County in the first flush of Evergreen statehood. By 1894, he was managing editor and part owner of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer newspaper.

Grant had also been appointed by President Benjamin Harrison (and fellow Ohioan) to serve as an American diplomat in Bolivia, and he likely had served in the U.S. Army, as several accounts of the IVANHOE refer to him as “Colonel Grant.” At least one newspaper story said that Grant was taking the cruise on the IVANHOE for his health.

In his History of the Puget Sound Country, historian and author William F. Prosser called Grant an “able and gifted editor.” Maritime historians Lewis and Dryden called Grant “one of the most prominent men in Washington.”

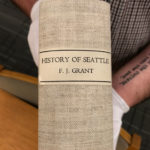

Along with being a journalist, Grant was also editor of one of the earliest local history books in what’s now the Pacific Northwest. The History of Seattle, Washington was published in 1891, and represents one of the first efforts to document the initial four decades of the city’s history.

In the book’s preface, Grant wrote:

We who reside in Seattle to-day do not regard ourselves as in any sense pioneers. The substantial city of the present apparently has little in common with the frontier settlement of twenty-five years ago. But to the resident of Seattle a century or two centuries hence, today will be linked with yesterday as the days of the pioneers. The time intervening between events that have marked the city’s history hitherto — the siege, the lynching, the anti-Chinese riot, the great fire — will appear less and less. In the long perspective of the future, the present and the recent past will seem almost as one. It is in this sense, therefore, that the present volume is said to contain only the history of the pioneer days of Seattle.

While the authors of The History of Seattle, Washington are listed as O.F. Vedder and H.S. Lyman, the only true writer of the book may have been H.S. Lyman.

In searches of online archives, O.F. Vedder looks to be some kind of itinerant promoter with a wide variety of interests. From the 1880s to the 1920s, Vedder pops up in nearly every corner of the United States. He edits a newspaper in Schenectady, New York; promotes a history book about Memphis, Tennessee; settles in St. Louis, Missouri; sells billboards in Chicago, Illinois; promotes a history book about Iowa; examines real estate in Portland, Oregon; promotes a history book about New York lawyers; and eventually becomes a breeder of Boston Terriers and works as an official of the American Kennel Club in California.

On the other hand, Horace Sumner Lyman came from a family of scholars. His brother William Denison Lyman wrote numerous Northwest history books. After the Seattle book, Horace would go on to write the four-volume History of Oregon: The Growth of an American State, published in 1903. Horace Lyman then passed away at age 49 in 1904, just a year after completing his masterpiece.

Unraveling the IVANHOE shipwreck

Lewis & Dryden’s Marine History of the Pacific Northwest provides more details about the loss of the IVANHOE, and why the discovery of the name-board in the sands near Willapa Bay was so mystifying.

[South of Cape Flattery on IVANHOE’s first full day at sea, a] heavy southeast gale sprang up, which increased in violence until it blew a hurricane, accompanied by rain and hail, and the weather was so thick that nothing could be distinguished at a distance of a few hundred feet. It cleared a few hours later, but nothing was seen of the IVANHOE [by the crew of the ROBERT SUTTON].

It’s unclear exactly when the IVANHOE was lost, but the ship was considered overdue sometime in early October when it didn’t arrive in San Francisco. Newspaper accounts in early November 1894 confirm the ship’s likely loss. Lewis & Dryden continued

Considerable wreckage was sighted along the coast for several weeks after the storm, but the first that was identified as belonging to the IVANHOE was one of her life-buoys [or ‘life rings’] picked up on Christie Island, Barkley Sound [along the coast of Vancouver Island, British Columbia]. This led to the belief that the vessel foundered soon after passing the straits [of Juan de Fuca], as she was seen going off shore to the southwest soon after the TYEE dropped her.

Lewis & Dryden go on to quote from a letter written by Commander Farenholt of the Thirteenth Lighthouse District:

… the particulars of the loss of the IVANHOE can only be surmises, but, to judge from the finding of this board at Willapa Bay, it would seem that the ship foundered much farther south than is generally believed. It is improbable that this [name-]board was carried inshore off or near Cape Flattery by a current setting to the southward, against strong southerly winds and currents. The topography of the coastline from [Cape] Flattery to Willapa [Bay] is such that a floating object drifting from the northward would probably have stranded at one of the many more prominent places than the beach at Willapa [Bay]. It is surmised that the IVANHOE sprang ‘a leak’ or that the hatches were crushed in by heavy seas. Pumps could not free her, and, with her heavy cargo of coal, she rapidly foundered. The condition of the board bears out this theory. There is no mar or defect to be seen. It had been strongly secured to the ship’s quarter. Had the vessel been in collision or been dismasted, I should infer from the locality where the board was placed that it would have at least been scratched or otherwise injured.

Farenholt offers no theory as to why the IVANHOE’s life-buoy had been found 150 miles from where the name-board was found; though, perhaps it may be “surmised” (to use one of Farenholt’s favorite word) that the life-buoy was somehow lost overboard a day or two before the ship met its ultimate fate.

Seattle group played a pivotal role in healing national wound

Checking with several local institutions in Washington and British Columbia that focus on maritime history, it’s clear that somehow, the only two artifacts from the IVANHOE that survived its loss – the name-board and the life-buoy – are also now lost themselves.

One clue can be found on the website for the firm that succeeded the old “Black Diamond Coal Company.” It reads, in part, that “the [name-board] and [life-]buoy were carefully preserved and sent to Washington Governor John H. McGraw. As one contemporary newspaper account stated, they ‘will be kept as a sad memento, the two silent witnesses of an irreparable loss.’”

Benjamin Helle at the Washington State Archives, where several boxes of Governor McGraw’s materials now reside, reports that the name-board and life-buoy are, unfortunately, not among the state’s holdings.

Another legacy of the loss of the IVANHOE, a memorial library of sorts in Frederic Grant’s honor, may, too, be lost.

Lost legacies

In the wake of his disappearance, Grant’s friends spent a few years raising money for books to create an American history collection at the University of Washington Libraries. It’s unclear if the collection was ever created, or, if it was, if it still exists.

One of the organizations consulted regarding the artifacts and potential sources of information about the IVANHOE was the Puget Sound Maritime Historical Society. The mostly volunteer group was founded in the late 1940s by a group of local maritime history enthusiasts, including prolific shipwreck-book author Jim Gibbs.

Ron Burke, who edited the Society’s journal “SEACHEST” for many years, wrote in an email that by 1894, the nearly 30-year old IVANHOE was “worn out” and “with that heavy cargo [of coal], if they got into trouble, they went down fast.”

That feeling that poring over and chatting about the myths and legends of Northwest shipwrecks is not as common as it once was around here was borne out a bit by further correspondence with Burke. When asked if there might be a particular expert, amateur or otherwise, who could shed more light on the fate of the IVANHOE, Burke was unequivocal.

“I’m afraid the people who could help us have passed away,” he wrote.

Which is a bummer, because those are exactly the kinds of people who can make kitchen table and front porch conversations around here so much more interesting.