Search underway for artifacts 72 years after Port Angeles shipwreck

Dec 4, 2019, 9:11 AM | Updated: 9:34 am

When a ship called the Diamond Knot went down near Port Angeles in 1947, it was carrying a precious cargo of canned salmon. The wreck inspired a unique salvage effort 72 years ago, and a current search is now underway for some specific artifacts in time for a new exhibit in 2020.

How King County’s first state rep disappeared in mysterious shipwreck

It was not long after midnight on August 13, 1947 when the Diamond Knot, a 338-foot ship loaded with 7.4 million cans of salmon and a crew of 38, was returning from Alaska and headed through the Strait of Juan de Fuca towards Seattle. It was foggy with zero visibility in the middle of the night, when something went wrong.

Another ship, the 455-foot Fenn Victory, was headed out of the Strait. About six miles off of Ediz Hook, the larger ship broadsided the Diamond Knot. The Fenn Victory punched a big hole in the side of the Diamond Knot, and lodged its bow into the deck of the smaller ship. The two vessels were stuck together and adrift, and the Diamond Knot was in serious trouble.

A distress call went out just after 2 a.m., and about 90 minutes later, the tugboat Foss No. 21 from Port Angeles arrived on the scene. The Diamond Knot took on water and was listing.

Mike Skalley worked in operations for Foss Maritime for nearly 50 years. He retired recently, and is something of an unofficial historian for the longtime local company who’s written books about its storied past.

Skalley says the Fenn Victory was able to get to port under its own power. This wasn’t the case for the Diamond Knot.

“They got a tow line up on the stern [of the Diamond Knot] and were towing as quick as they could to get it onto the beach around Crescent Bay,” Skalley said. “They towed for a couple hours, and at one point, the ship continued to get lower in the water. They took the crew off, and before they could get it beached, the ship sank.”

The Diamond Knot went down in about 135 feet of water less than a mile off shore in the mouth of Crescent Bay, west of Port Angeles. The value of the cargo in 1947 – those 7.4 million cans of red salmon – was $3.5 million, or roughly $40 million in 2019 dollars. This was a time of post-war food shortages around the world, so the cargo was also precious beyond its monetary value.

The salmon salvage

Fireman’s Fund Insurance Company paid out the claim to the owner of the lost cargo, but then went about salvaging all the canned salmon to try and recoup their losses. To do the job, they commissioned San Francisco marine salvage company Pillsbury & Martignoni to build a heavy duty barge-mounted vacuum machine.

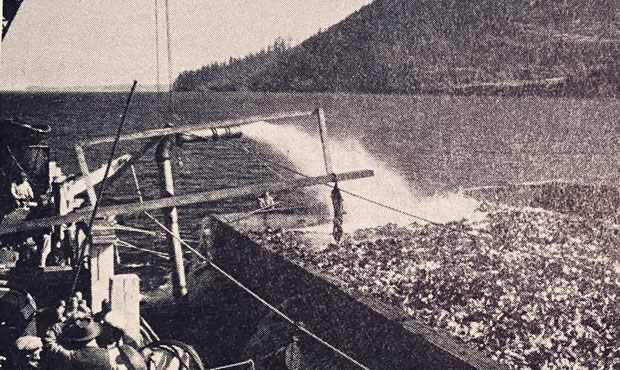

The operation also involved sending men down in diving suits to cut open the side of the Diamond Knot and then vacuum up the millions of cans. The work, in which Foss also played a significant role with their tugs and barges, lasted from August to the end of October.

Fireman’s Fund also commissioned a promotional film about the project, which documented every step in the process in justifiably glowing terms.

As the 12-inch diameter siphon hoses of the vacuum device first spewed water and then sunken treasure, the film’s narrator exclaimed, “Up they come … torn and partially disintegrated cartons. Then, golden cans of salmon … thousands of them … up from the bottom of the sea!”

The salvage operation was indeed something of a technical marvel, with the biggest challenge being to find a way to anchor the vacuum barge in place over the wreck, in spite of the wind, tides and current.

Alongside the vacuum barge, the crew would moor cargo barges that could hold between 300,000 and 500,000 of the one-pound cans. When the siphon was working at peak efficiency, it pumped a thousand gallons of water and 800 cans a minute.

Over the course of the project, a total of 20 barges full of cans were hauled to canneries in Seattle, Friday Harbor, and Semiahmoo.

Re-canning the salvage

At the canneries, project engineers built a fairly complex mechanized system to transfer the salvaged salmon from the old cans and repack in completely new cans. According to the film’s narrator, to make sure the old salmon hadn’t gone bad, they used an infallible method.

“Here, a double row of highly trained girls transferred the fish from the original can to a new can,” the narrator says. As the film shows a woman standing alongside a conveyor belt, and bending at the waist to place her nose perilously close to the open cans of salmon moving past, the narrator continues, “The fish and empty can were then carefully smelled to detect any evidence of spoilage which might have taken place without the cans showing this condition.”

The repacked salmon, which had, of course, been thoroughly and completely cooked when it was originally canned in Alaska, was subjected to a second trip through the oven, and was cooked for 90 minutes at 240 degrees.

Of the roughly 5 million cans recovered from the Diamond Knot, about 73 percent were able to be repackaged. These new cans were then labeled for sale and shipped to points unknown for distribution.

Your chance to help out

And this is where the Puget Sound Maritime Historical Society (PSMHS) comes into the story. PSMHS has in its collection a handful of mechanical artifacts from the Diamond Knot that divers retrieved in the 1970s. Because the group is creating an exhibit about the Diamond Knot that will open sometime late next year at MOHAI, what PSMHS director Alicia Barnes would really like to find are some examples of the various labels that were applied to the new cans of Diamond Knot salmon.

Searching for lost clues about the winter of 1861-1862

Barnes has a photo of at least one variety of a Diamond Knot salmon label that was dedicated to Foss Tugs for their role in towing the ship and in helping with the salvage operation.

“The salmon can labels that they re-canned them with says ‘Diamond Knot salmon, twice caught, twice canned, twice labeled, twice packed. Given to you with our best wishes twice over,’” Barnes said, reading from the photo. “And it has the Foss ‘Always Ready’ logo off to the side of that little phrase.”

Based on the wording, this label may have been applied to just a small number of “commemorative cans,” perhaps given to Foss employees. If this is the case, no one is sure just how many of this particular variety were produced.

Alicia Barnes says that there might be one of these Foss Diamond Knot labels tucked away somewhere in the Puget Sound Maritime collection, but they have not yet been able to locate it as yet.

What Barnes and Mike Skalley are hoping is that someone hung onto one or more of any variety of the special Diamond Knot cans or at least the old labels. If you think you might have one, send an email to fbanel@kiroradio.com.

As if the sound of twice-cooked canned salmon wasn’t unappetizing enough, Barnes shared one more tasty morsel about the Diamond Knot salmon label mystery.

“The only other thing is that there’s sort of an urban legend that some of the canned salmon that wasn’t deemed good enough for human consumption but wasn’t completely off, was re-canned and sold as cat food. I don’t know if it’s true but it’s sort of it’s a rumor out there, anyway. If anybody has proof of that, that would be awesome to find.”