Danny O’Neil: Race has no place in disease names

Mar 26, 2020, 5:02 PM | Updated: Mar 27, 2020, 11:02 am

(Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

(Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

A fear of being punched isn’t the only reason my wife wears a face mask when she leaves our apartment.

She thinks it will keep her a little more anonymous, that it makes her a little less threatening. She wants our neighbors in our 50-floor high-rise to feel safe. The doormen, too, and anyone in the grocery store. The mask won’t keep her from contracting COVID-19, but maybe it will keep others from fearing she might pass it along.

She’s not just wearing it for their protection, though.

My wife is Asian-American. She’s worried about being blamed, even targeted. Less than two weeks ago an Asian woman was attacked in Midtown Manhattan. That’s about 25 blocks south of where we live, half a dozen blocks from where my wife works. The victim was a 23-year-old student from Korea. As she walked down the street, another woman shouted, “Where’s your (expletive) mask?” and accused her of getting people sick. She grabbed the victim by the hair and punched her. The student suffered a dislocated jaw.

These are scary times for everyone. We’re worried about the country’s healthcare system. We’re worried about the economy in general and our jobs in particular, and to some degree we’re afraid of getting sick or those we know and love becoming ill. But for Asians and Asian-Americans there’s an extra burden. They also have to worry about being targeted for harassment, even hate, for a disease they’re no more responsible for spreading than anyone else.

So when President Donald Trump began calling COVID-19 the “Chinese virus” last week, I wasn’t offended so much as I was worried. Concerned that it would only increase the animosity and hate directed at people of Asian descent. People who look like my wife and her family.

This scenario is precisely why the World Health Organization issued guidelines in 2015 to doctors, government leaders and media organizations, calling on them to be more careful when labeling a disease. Specifically it said to avoid using a specific region, a person’s name or referencing a population in the name. Stereotypes can develop, stigmatizing those in the region or among that population. And though COVID-19 originated in the Wuhan region of China, its global spread is neither limited to nor driven by people of Asian descent. It’s not concentrated in local Chinatown neighborhoods or in Chinese restaurants.

Given that rationale, it’s hard to think of a really good reason to call it the Chinese virus, the Wuhan flu or any other Asian locale not to mention the people trying to make decidedly unwitty plays on words involving martial arts disciplines.

And yet as the President stood by his terminology last week, the attempts to point out the problematic nature of his language were met with very aggressive pushback. Here’s a sampling:

No one cared about this before Trump said it!

Actually not true. On Feb. 13, the Asian-American Journalists Association issued an advisory to media outlets around the country, specifically citing the WHO guidelines for disease names.

Michelle Ye Hee Lee is the current president of AAJA, and I spoke to her Monday. She explained that the organization had been monitoring the images and language used in the coverage not just in the United States but all over the world. The advisory was designed to address three primary trends that AAJA had identified:

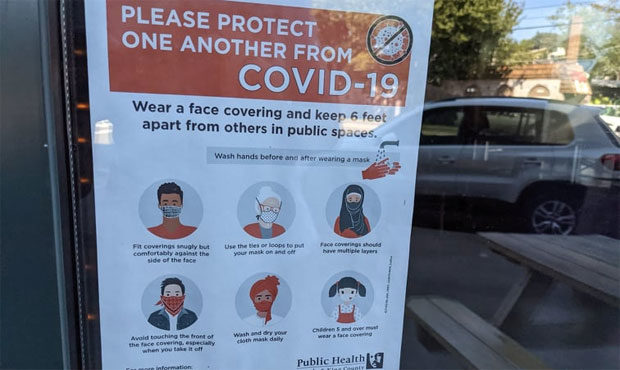

• Pictures of Asians wearing masks, something that is commonly done to combat pollution in East Asian countries and predates the COVID-19 outbreak.

• The use of images from local Chinatown neighborhoods in stories about the virus in general. Those images should only be used in stories that detail that neighborhood, specifically, and not for general stories about the virus and its implication.

• Avoid using geographic descriptions or terms that would apply to a group of people, citing the WHO guidelines from 2015. Remember: This was first issued on Feb. 13.

B-b-b-b-but I saw a Washington Post headline that said, “Chinese virus” and nobody said that paper was racist!

You’re right. That phrase was in an A1 headline in that paper in January. It was said on many TV broadcasts, too. And in other publications. That’s why the advisory went out, and then something encouraging happened: Those phrases and images began to disappear from the coverage. Why? Because news organizations largely heeded the message because they didn’t want to use language that would encourage or possibly reinforce prejudicial assumptions and stereotypes. The issues didn’t vanish entirely. There were still instances that needed to be addressed, but newspapers and television stations became more thoughtful in their language and imagery.

This is how it’s supposed to work, right? An issue or action causes harm or creates a potential threat. Sometimes it’s deliberate, other times inadvertent. A group points out the harm and requests a change, and the behavior gets modified to eliminate or lessen the harm being caused to that group. And if – after hearing those objections – the actions continue? Well, that’s a decision that you’re making and thereby showing you don’t respect the concerns that have been raised, and more specifically, the people who are making them.

What about the Spanish Flu of 1918???

Well, I can’t speak to the thought process that led to that or the media reaction in general GIVEN THAT I WAS NEGATIVE-56 YEARS OLD AT THE TIME. But honestly, that seems fairly awful and also misleading given the fact that most evidence points to the virus originating in Kansas. It was also 1918 and there were a lot of things considered acceptable then that would be greeted with condemnation now.

A mistake from the past isn’t valid grounds to repeat it in the future, and hopefully we’ve learned the dangers naming a disease after a certain group of people can have. Same goes for the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS). The point is not that we should always be perfect but that we should learn to recognize issues that our actions and words cause and adjust our behavior.

But he’s really talking about the ruling party, the Chinese Communist Party!

OK. It’s fair to not just scrutinize but criticize the actions of China’s ruling party in its reaction to the COVID-19 outbreak. But calling it the “Chinese virus” is an unbelievably poor way to send that specific message. There are 1.4 billion people in China, and there are another 50,000,000 people around the globe who would fall into that demographic category. But let’s be honest, too. The kind of people who are going to make racist generalizations aren’t usually the kind of people to carefully differentiate people of Chinese descent from Chinese citizens, let alone distinguish between people from Korea, Japan or any number of Asian countries.

Let’s pause the linguistic arguments to look at the broader context of what was occurring across the country while this debate was occurring.

Jiayang Fan, a writer at the New Yorker, was profanely berated outside her own apartment while speaking on the phone to her mother. She said she wasn’t mad, wasn’t angry. She was afraid. This guy now knew where she lived. A 28-year-old Korean-American was spat at and coughed upon in a bathroom at Penn Station. And in Los Angeles, a CNN anchor described being subjected to a racial slur as she was working.

It occurred locally, too. An Asian-American walking her dog in Wallingford was yelled at. Two different teachers described having to talk to their students about things that were being said to classmates about the disease. A Japanese-American woman whose family has been here for four generations had two people jump away from her, covering their faces at the Covington Costco.

Here were documented instances of Asians and Asian-Americans being stigmatized at a time the president was using language that was criticized because it would reinforce that stigma, and a not-insignificant number of people across the media and in the country at large were using their critical-reasoning faculties to neuter, even mock criticism of the president without thinking for a second on the potential impact on Asians and Asian-Americans.

It wasn’t just sad. It was absolutely infuriating, and the only reason it stopped was because the President stopped using the term “Chinese virus” this week. He Tweeted about the need to protect the Asian-American community, and during Monday’s press conference addressed the reports of harassment and hate.

“It seems that there could be a little bit of nasty language toward the Asian-Americans in our country,” Trump said. “And I don’t like that at all. These are incredible people. They love our country. And I’m not going to let it happen.”

I felt relieved, even grateful to hear it. Not because it was some extraordinary act of courage. Having a president speak out against the harassment of his citizens because of their race should be a given in 2020. But given what I saw and heard last week, had Trump continued to use that terminology, plenty of people would have continued to defend his right to do so even as instances of harassment – and perhaps worse – continued.