How a dog helped FDR win the election of 1944

Apr 15, 2020, 10:59 AM

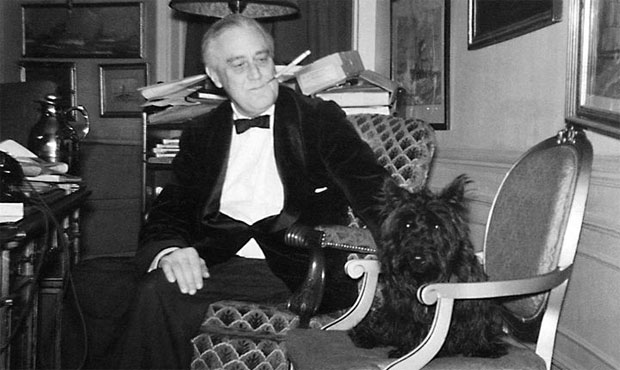

President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1944. (National Archives)

(National Archives)

With Bernie Sanders dropping out a few days ago, the matchup for this year’s presidential election is now pretty well set. And now, with the pandemic, a campaign that was already one of the strangest in memory is making some people recall the wartime election year of 1944.

It would be irresponsible to draw too many comparisons between our present situation and the World War II homefront, but this pandemic – with empty shelves, masks, limitations on activity and the constant uncertainty about what comes next – comes closer than any other time that most people have lived through.

Like 2020, 1944 was a presidential election year. It was also 12 months filled with big international developments and sometimes terrifying, sometimes reassuring news from overseas — the Allied landings at Normandy and the liberation of Western Europe, but also V-2s guided missiles raining down on London. And the war wouldn’t be over until 1945.

A Gallup poll in 1943 said that heading into the election year, Americans were concerned about domestic issues after the war like jobs, as well as avoiding another war through some kind of international organization, like what would emerge as the United Nations.

Franklin D. Roosevelt was the Democratic president. He’d been first elected in 1932, and had steered the country through and out of the Great Depression, and through the first nearly three years of America involvement in World War II. In 1940, he’d been elected to an unprecedented third term, defeating Republican business leader Wendell Willkie. In 1944, the Republican challenger was New York Governor Thomas Dewey.

As a wartime president in 1944, FDR subtly and often deployed his “Commander in Chief” role as a campaign tool, and was understandably highly visible in newspapers and newsreels fulfilling presidential duties related to the war, and spoke often on national radio broadcasts. It wasn’t a stretch or disingenuous to consider FDR a wartime presidents; scholars and historians agree that FDR was hands-on for the Allies in the battles in Asia and Europe.

In 2020, scholars have noticed attempts to adopt similar theme during the pandemic.

Betty Winfield lives in Seattle. She’s Professor Emeritus at the University of Missouri, and an expert on FDR and the media.

“I think it’s interesting that the current White House is calling this a war and taking that kind of ‘commander-in-chief’ moniker, because that means that we can do things we probably wouldn’t do if it were a peace time situation,” Winfield said. “So it gets the attention and even though some of the networks and the channels are not covering those daily briefings like they did it, it still gets the attention of a lot of others and even the major networks are at least referring to it almost nightly in their news.”

But in the summer of 1944, FDR stumbled a little. He took a tour with the Navy to Hawaii and Alaska in July and August. When he returned to the Lower 48 – after being absent from the airwaves for a month – the president gave a nationally broadcast speech from the deck of a Navy ship in Bremerton. As a recording of the speech demonstrates, the words were right, but the delivery was somehow off, and not up to the standards of the “Radio President,” as FDR had been dubbed.

At the time, nobody said publicly that FDR looked and sounded ill, but it emerged much later that he had indeed suffered some kind of cardiac problem during the Bremerton speech. While critics kept quiet about his health, that 1944 Pacific trip was criticized by some Republicans as a campaign tour disguised as presidential business, all at taxpayer expense.

Republican candidate Thomas Dewey was considered handsome and was an able, if not a fiery, orator. Fellow Republican Robert Taft said of Dewey, who had risen to fame as a prosecutor taking on organized crime in New York, that he could be “arrogant and bossy.” Another critic quipped that Dewey “could strut while sitting down.” At age 42, others worried he was too young to take on the role of wartime president.

The presidential campaign season was shorter in the mid-20th century, with nominees often emerging at summertime conventions – rather than after springtime primaries – and serious campaigning taking place mostly from August until the November election.

Looking at the old newspaper clippings and listening to vintage radio broadcasts, it seems that wartime realities overshadowed — or at least dulled the edges — of the quadrennial exercise of American democracy.

It’s not as if the issues at stake – jobs at home, avoiding another war after the current one was over – meant any less, it’s more that the life-or-death struggle overseas made the policy differences between Democrats and Republicans seem smaller than usual, and the political maneuvering seem more distasteful.

David Jordan wrote a book in 2012 called “FDR, Dewey, and the Election of 1944.”

The campaign season “was a little shorter because we were at war, and there wasn’t the big buildup for getting the candidates nominated at the convention,” Jordan said. “After the conventions, they took it easy for a while, and then there was some traveling around and then the campaign got a little more exciting.”

For Thomas Dewey, this meant a western campaign tour, including a swing through Washington by train in late summer.

Dewey gave a speech in Spokane, and then came to Seattle where he spoke at the old Civic Auditorium (now McCaw Hall) to an overflow crowd on September 18, 1944. His Seattle event was carried nationwide on radio by CBS and locally by KIRO Radio.

Governor Dewey then headed south, making stops in Portland, San Francisco and Los Angeles. South of Seattle, near Castle Rock, Washington, the train carrying Dewey and his entourage struck the rear of a parked train; there were only minor injuries reported.

Listening to audio of Dewey’s Los Angeles speech, the candidate comes across as polished but not exactly charismatic. The words seem platitudinous, and, because of the war, this meant a certain amount of restraint when it came to being critical of the sitting president.

“It was kind of laid back,” David Jordan said of Dewey’s rhetoric. “He was critical, but he wasn’t disastrously so.”

A few days after Dewey’s California speech, FDR addressed a national gathering of the Teamster’s Union in Washington, DC. Viewing the newsreels and listening to the audio of this appearance, it’s clear that President Roosevelt was feeling better than he had felt in Bremerton six weeks earlier.

The remarks to the Teamster’s – which became known as the “Fala Speech,” for FDR’s Scottie dog – are credited, on almost the eve of the election, with sweeping aside any worries about the president’s health.

“These Republican leaders have not been content with attacks on me, or my wife, or on my sons. No, not content with that, they now include my little dog, Fala. Well, of course, I don’t resent attacks, and my family doesn’t resent attacks, but Fala does resent them. You know, Fala is Scotch, and being a Scottie, as soon as he learned that the Republican fiction writers in Congress had concocted a story that I had left him behind on the Aleutian Islands and had sent a destroyer back to find him — at a cost to the taxpayers of two or three, or eight, or twenty million dollars — his Scotch soul was furious. He has not been the same dog since. I am accustomed to hearing malicious falsehoods about myself, such as that old, worm-eaten chestnut that I have represented myself as indispensable. But I think I have a right to resent, to object to libelous statements about my dog.”

Is it urban legend, or did the “Fala Speech” really make a difference in the 1944 election?

“It really did [make a difference],” David Jordan said. “FDR had been taking it easy as far as campaigning. The ‘Fala Speech’ got a lot of press and it was kind of a turning point in the campaign.”

Jordan says that by the president defending his dog with humor in the face of Republican criticism, along with his taking part in a rainy day parade in New York City (and captured by newsreels) helped put voters at ease.

“The rainy day in New York put to rest the whisperings about his health even though [the whisperings] were right,” that FDR was in physical decline, Jordan said.

“After that FDR, was on the go and moving ahead” toward the November 7 election, Jordan said.

Roosevelt won the 1944 election and an unprecedented fourth term by a fairly wide margin, with about 55% of the popular vote.

There were also local races here in Washington in 1944, of course. When the votes were tallied, Washingtonians had said “no” to a state income tax (for neither the first nor the last time) and nixed a state social security system, too. Incumbent Republican Governor Arthur Langlie lost to Democrat (former Everett optometrist and current sitting US Senator) Monrad C. “Mon” Wallgren by a narrow margin.

Governor Langlie had welcomed Thomas Dewey to Seattle and spoken alongside him at the Civic Auditorium campaign event.

Governor Langlie’s grandson Art Langlie is a student of his family’s political history. He says that his grandfather, who in 1944 had served just one term, was the victim of partisanship in the election that year.

“What he did, which was typical of him, was that instead of going through and cleaning house and [replacing the head of] every government agency in Olympia [when he was elected in 1940], he went through and evaluated who he thought was doing a good job,” Langlie said.

“And he left a lot of people in place in state government that he felt were doing a fine piece of work … [then] when he went to run again for the next election in 1944, not all of them were kind to him,” Langlie said.

“My dad always said that they basically turned on [my grandfather] when he came to run again because a lot of them were Democratic holdovers,” Langlie said, while acknowledging there were probably other factors at play, too.

Whatever the reason, losing the 1944 election wasn’t the end of the world, or an end to his political career, for Arthur Langlie.

“He was probably unhappy about the fact that he wasn’t going to continue to do what he thought was the right thing for the state of Washington,” Art Langlie said. “[But] he would not have been someone that would have been beside himself; I think he would have just said ‘Well, that is what it is.’”

The defeated Arthur Langlie went back into the Navy for the remainder of the war, and opened a legal practice in Seattle. But four years later, he ran again for governor – perhaps, his grandson says, inspired by that 1944 election loss.

“I’m sure that it probably, in the end, helped make his decision to go run again,” Langlie said.

And Arthur Langlie did defeat Governor Mon Wallgren in 1948, and was re-elected for a third term in 1952. Only one other person – Governor Dan Evans – has served three terms as leader of the Evergreen state (which Jay Inslee will attempt to match later this year).

Thomas Dewey also came back in 1948 as the Republic nominee for president, and came mythically close to defeating President Harry Truman.

Truman – who had replaced Vice President Henry Wallace on the ticket in 1944 – had become president when FDR died of a cerebral hemorrhage on April 12, 1945, less than three months after being inaugurated for his fourth term, and just weeks before the end of the war in Europe.

You can hear Feliks every Wednesday and Friday morning on Seattle’s Morning News and read more from him here. If you have a story idea, please email Feliks here.