How Spokane’s ‘Buffalo Soldiers’ saved Idaho town from historic 1910 blaze

Sep 23, 2020, 10:20 AM

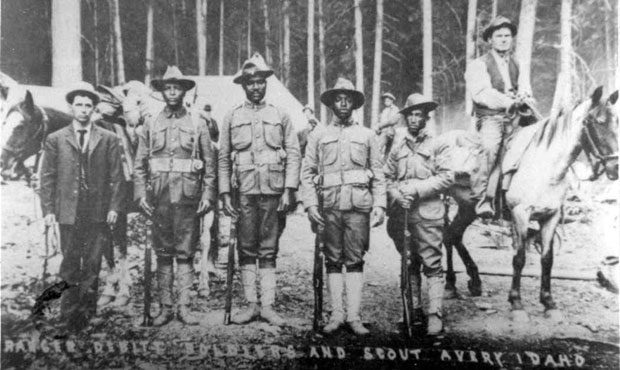

Black soldiers stationed at Fort Wright in Spokane were sent to Wallace, Idaho and Avery, Idaho to help fight the wildfires known as the "Big Burn of 1910," and helped save Avery from the flames. (Museum of North Idaho)

(Museum of North Idaho)

Wildfires are nothing new in the Northwest, and the “Big Burn of 1910” in Idaho and Montana is still remembered as one of the worst disasters in the region’s history.

What’s not remembered so much is that one group sent to battle the blaze was a company from the 25th Infantry, a regiment of Black soldiers, most of whom were from the American South, but who were stationed at Fort George Wright in Spokane.

The Big Burn of 1910 has been the subject of books and documentaries – notably by Northwest author Timothy Egan and from PBS – for the centennial 10 years ago. The fire in late August of that year was actually a series of blazes mostly in Idaho and Montana, though partly in British Columbia and Washington, too. A total of an estimated three million acres burned, and at least 87 people died after what had been an exceedingly dry spring and summer.

The science of forestry and the Forest Service as a federal agency were relatively new in those years. There weren’t enough firefighters to meet needs, and President Taft authorized the Army to help.

Black troops — known as “Buffalo Soldiers” in the days when the U.S. Army was segregated from 1866 to the early 1950s — were sent by train from Fort Wright in Spokane to Wallace, Idaho.

Charles Williams is with the National Buffalo Soldier Museum in Houston, Texas. He says that what the soldiers found when they got to Idaho was not good.

“If you’ve ever visited Wallace, Idaho, you will notice that it sits down in a valley between mountains and surrounded by mountains, and the timber on those mountains are as thick as the hair on the dog’s back,” Williams said. “Now, imagine you’re in a valley, you’re looking up all around you, and it’s a ring of fire totally all around you because the forest is on fire.”

From Wallace, the Black troops were sent to help keep with firefighting efforts and to the peace in nearby Avery, a railroad town which had became a center of the effort to fight the fires.

John MacLean has written several books about wildfires, and he comes from a family with a long history in Montana. His father was the writer Norman MacLean who wrote classics like A River Runs Through It and Young Men and Fire.

MacLean says the Buffalo Soldiers weren’t exactly welcomed in Avery – though they ultimately played a vital role in evacuating and then saving the town.

“There were some trains [in Avery] to get women and children out of there,” MacLean said. “And the Black troops, they’re new to Avery [and] most of the people there had seen maybe a couple of Black [people] in their lives, and they have the usual prejudices.”

Those prejudices, MacLean says, included “’these guys are drunks, they’re on dope, they’re going to tear everything apart, they’re no good.’” And these sentiments were expressed to the soldiers by many Avery residents, MacLean says.

When it came time to evacuate women and children from Avery, the soldiers from Fort Wright had the unpleasant duty of making sure that able-bodied men were kept off the train, since they were needed to stay behind and fight the fire.

Not long after that, when only the Black soldiers remained in Avery, it was their turn to evacuate by train. But fires blocked their path.

MacLean says they headed back to Avery.

“And they decided to build a backfire,” MacLean said, which is a small blaze designed to rob a larger blaze of fuel and prevent it from spreading.

“They went across the river that’s there, the St. Joe’s, and they built a backfire at the base of some steep hills and mountains to run it into the main fire,” he continued. “And they basically stood their ground. They reported afterwards [that] if the wind hadn’t cooperated, if the wind had done something weird at that point, they could have all been killed.”

“That didn’t happen,” MacLean said. “The backfire basically worked and they saved the town of Avery.”

There was plenty of heroism in fighting the 1910 fire, including the exploits of Forest Service Ranger Ed Pulaski, but John MacLean says the Black soldiers from Fort Wright stand out more than a century later for what they faced beyond just the danger from the fire.

“There’s a lot of anecdotal material – quotes from people afterwards – saying, ‘My whole view of the Negro race was entirely changed by these guys,’” MacLean said. “’They were white to the core’ was one of the things said, which is about as backhanded a compliment as you can get, but they meant it in a complimentary way.”

Residents of Avery and others went from being apprehensive to appreciative, MacLean says, expressing sentiments along the lines of “’they may have been Black, but there was no yellow there.’ They were very brave.”

And that bravery is what decades earlier helped inspire the “Buffalo Soldiers” nickname, according to Charles Williams of the National Buffalo Soldier Museum. The name originated with the Native American tribe known as the Cheyenne, who skirmished with Black soldiers on the plains in 1867, and who found them to have the fighting spirit of buffalo, as well as hair that, in some cases, resembled a buffalo mane.

“Actually, the translation [of what the Cheyenne called the soldiers] was ‘wild buffalo,’” Williams said, “which later became ‘Buffalo Soldier,’ … so, generically all Black soldiers during that period were considered to be, or [were] called, Buffalo Soldiers.”

Apart from sections in a handful of books about 1910 fire, the story of the 25th Infantry Regiment’s role is not something that is widely known or recalled 110 years later.

Dr. Quintard Taylor, UW history professor emeritus and founder of Blackpast.org, said in an email that he would welcome more research and more efforts to understand and share this aspect of Buffalo Soldier history.

“Their story needs to be told,” Dr. Taylor wrote, “especially now with the fires raging in the West.”

John MacLean agrees that the 25th Infantry’s role in the fire represents a great opportunity for a writer.

“I wish somebody would do a book about it,” MacLean said.

Charles Williams says that beyond the fire, Buffalo Soldiers contributed to America in countless ways, especially in the West in the 19th century and early 20th century. What they accomplished in Idaho, Williams says, is merely a piece of their storied history.

“I consider it to be one of the many things that they did that was not widely recognized, except for in those areas where they occurred,” Williams said.

And while recognition in those areas like Wallace and Avery might have taken awhile, North Idaho of the 21st century has enthusiastically embraced Buffalo Soldier history.

Dave Copelan of the Wallace Chamber of Commerce says this appreciation began in earnest during the 1910 fire centennial observances in 2010.

“The stories of the Buffalo Soldiers’ experience in North Idaho is an amazing under-told story,” Copelan said. “When we first stumbled upon it, we thought ‘This is gold.’”

Copelan says that multiple museums in the Wallace area now include exhibits that touch on the Buffalo Soldiers’ role in fighting the 1910 fire. Wallace has also hosted events related to the “Iron Riders,” bicycle-mounted Black troops who pedaled the hills and plains of the West on heavy, one-speed two-wheelers more than a century ago.

Copelan also hopes that someday a portion of an envisioned cross-country rails-to-trail path – the Great American Rail-Trail — will honor the Iron Riders, and follow the North Idaho trail known as the Route of Hiawatha, named for the Milwaukee Road’s Chicago-to-Seattle train.

“This is just an incredible tale that needs to be told over and over again,” Copelan said.

You can hear Feliks every Wednesday and Friday morning on Seattle’s Morning News and read more from him here. If you have a story idea, please email Feliks here.