How the Seattle General Strike of 1919 shut down the city

Jan 23, 2019, 11:57 AM | Updated: 6:01 pm

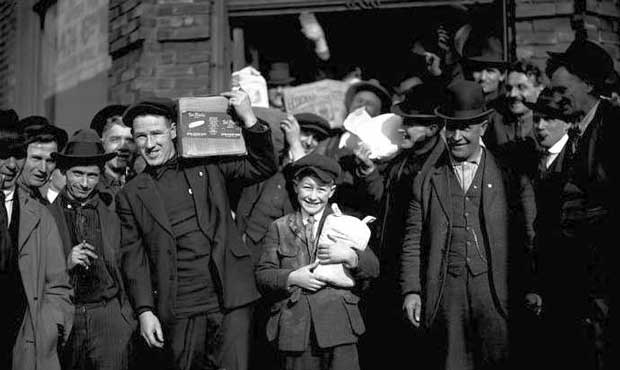

Men and boys helped deliver groceries during the Seattle General Strike of February 1919. (MOHAI)

(MOHAI)

David Jepsen isn’t a filmmaker. He’s a college professor and textbook author who teaches Pacific Northwest history. But even though he’s not a filmmaker, Jepsen’s new documentary about the February 1919 Seattle General Strike will premiere early next month to mark the centennial of the event.

RELATED: Architect who argued against Alaskan Way Viaduct in 1947

RELATED: Seattle history captured in ’70s/’80s movies

“You can’t teach Northwest history without talking about the labor movement, and the Seattle General Strike is just one event in many,” Jepsen said. “But there’s not a lot of tools available (to teach college students about it). Young students today, they like video, they like moving pictures, and they’re very visually oriented, but there’s no good film available on this topic.”

A few years ago, it was one of Jepsen’s students who inadvertently inspired him to make a film.

“The final straw for me was, I’m lecturing to my students on labor history in the Northwest, talking about the radicalization of workers and the rise of the union movements, and I had a student from the back of the room raise his hand and say ‘Mr. Jepsen, what’s a union?’” Jepsen said.

“I just saw this as an opportunity to put the General Strike in context, as well as to raise awareness of unions and labor issues in general,” he said.

The resulting one-hour film, “Labor Wars of the Northwest,” will be shown at the Museum of History & Industry (MOHAI) on Saturday, Feb. 2. The screenings and post-film discussions are free with regular MOHAI admission.

Seattle General Strike of 1919

The General Strike in Seattle is considered to be the first of its kind in the US. It’s known as a “general strike” because workers from all kinds of industries and services walked off the job on the morning of Thursday, February 6, 1919. Nearly 65,000 workers were involved, or 20 percent of the city’s population.

The Seattle General Strike was preceded by a strike against shipyards on the Seattle waterfront in January 1919. (Paul Dorpat)

Jepsen says the spark came from World War I, which had just ended in November 1918, and from disgruntled workers in the shipyards that used to line much of Elliott Bay near Pioneer Square.

“During the war they had asked for a raise,” Jepsen said. “The ship workers, the dock workers, had been promised a raise — ‘Get us through the war, get us through World War I, help us get our ships out, and we’ll give you a raise then.’ Well, of course, when the war ended, the demand for ships and defense equipment dropped steeply and the owners reneged. They refused to give the workers a raise. So they struck in late January of 1919.”

But the labor action didn’t remain in the shipyards.

“Following [the shipyard] strike, there were a whole series of sympathy strikes. Cab drivers, railroad workers, electrical workers, barbers, waiters, waitresses,” Jepsen said. “Eventually, 125 unions joined together, almost 65,000 workers, and essentially shut down Seattle for six days.”

Jepsen says that the whole situation was, in reality, many years in the making.

“The General Strike was really the culmination of almost 30 years of conflict,” Jepsen said. “Workers started pouring into the region in the 1880s with the arrival of the railroads. The Pacific Northwest is a long way from anything, and before the railroads there just wasn’t the transportation to move products, to move logs, coal, gold silver.”

“When the Northern Pacific [Railroad] arrived in the late 1880s, it unleashed a torrent of economic activity,” he said. “And that brought in jobs, and thousands of workers came here, and right from the start, there’s conflict over wages and working conditions hours.”

“So we need to look at the Seattle General Strike as really the culmination of three decades of conflict between owner and worker,” he added.

Seattle’s Mayor Ole Hanson called out the National Guard and mobilized the police, plus a few thousand additional temporary volunteer officers. But the strike was actually fairly peaceful.

“It was a very well organized strike in terms of … keeping people off the streets,” Jepsen said. “The organizers knew that strikes often lead to violence. Picketing, marching, rioting these kinds of things, and so they basically told the workers to stay home. So that’s a success in that they managed to avoid any sort of bloodshed.”

Those same strike organizers worried about disrupting vital services.

“Who’s going to turn on the electricity? Who’s going to collect the garbage? There was worry about the hospitals,” Jepsen said. “Who’s going to deliver milk for the babies?”

“(Strike organizers) came to an agreement with the city over the kinds of essential services that would not be affected,” he said. “They organized milk deliveries. So at the end of the day, the babies got their milk, the hospitals stayed open, essential services like electricity and running water were kept running.”

Downtown Seattle streets remained relatively quiet during the General Strike of February 1919. (UW)

Ended with a whimper

But ultimately, Jepsen says, the massive walkout just didn’t last.

“It ended kind of with a whimper,” Jepsen said. “The organizers did not anticipate the hostility to the strike. First of all, all the major media, the Seattle Times, the P-I, other papers came out very strongly against the General Strike. Additionally, Mayor Ole Hanson came out very diligently against the strike.”

Mayor Hanson had initially been sympathetic with workers.

“[He] sat in on early meetings in negotiating of the strike,” Jepsen said. “But when he couldn’t get his way, when the unions insisted on going on, he stormed out of the meeting and called the governor.”

“So, between the hostility of the media and the resistance by city government, it became clear after four or five days that the strike wasn’t going anywhere,” he said. “Workers wanted to go back to work, they wanted to get paid. And so one union at a time started pulling out, and then after six days they officially ended the strike.

Jepsen says that a hundred years later, historians still can’t agree on what, if anything, the General Strike accomplished. He says the worst fear at the time, which even someone like Seattle Mayor Ole Hanson shared, was that the General Strike was a precursor to all-out revolution. That’s how it had worked in Russia a few years earlier.

“So that was the fear, that somehow these union radicals, these thousands of workers aimed at a revolution,” Jepsen said. “There’s no real evidence that they planned that. But on the other hand, it’s hard to say what they wanted to accomplish.”

“Certainly the ship workers and dock workers wanted their raise,” Jepsen said.

Though, the workers didn’t get that raise.

“But could the union organizers have expected to settle wage disputes with 125 different unions?” he said. “That’s not realistic, that was never going to happen. So in that respect, it was a failure.”

Union success

But Jepsen has a different perspective.

“If we look at it more closely, at the end of the day, really what those workers wanted was to be heard,” he said. “They wanted their grievances aired. They wanted some respect and some dignity and some understanding. In that respect, I think we can call it a success.”

“Certainly, the world was watching. Newspapers throughout the United States and in many western countries were covering the strike,” Jepsen said. “Media came from all over the world to see what was going on. So, in terms of having their voice heard, it was a success.”

Jepsen isn’t the first academic to be inspired by the Seattle General Strike. In the late 1970s, sociologist Rob Rosenthal collected dozens of oral history interviews with people who had taken part or been affected by the walkout. In addition to his academic research, Rosenthal composed a rock opera called “Seattle 1919.”

“Labor Wars of the Northwest” premieres at MOHAI with two screenings on Saturday, Feb. 2 at 1 p.m. and 2:30 p.m., each followed by a discussion with filmmaker David Jepsen.

More from Feliks Banel