Comparing the Great Depression in Washington to the COVID-19 crisis

May 13, 2020, 9:05 AM | Updated: May 14, 2020, 8:42 am

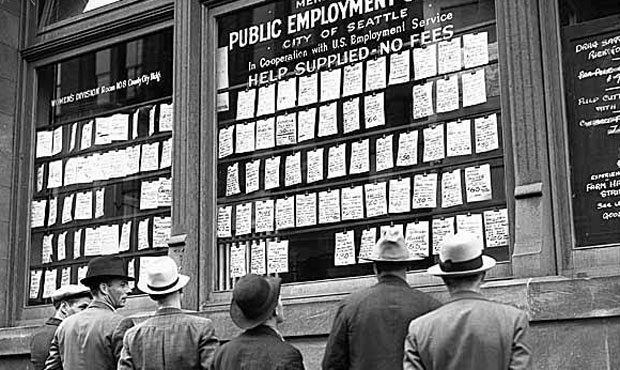

Men searching for jobs during the Great Depression review listings at the City of Seattle's Public Employment office in 1936. (MOHAI)

(MOHAI)

It’s no exaggeration to say that the unemployment rate is off the charts because of the COVID-19 pandemic. And it’s no stretch to say that the last time the job numbers were this bad in Washington was during the Great Depression in the 1930s.

The economy in the Northwest in the 1920s had not yet transitioned to the manufacturing powerhouse that would develop during World War II with Boeing, Paccar, and other emerging industrial giants. In the decade after World War I, timber was still king in the Northwest, with fishing and agriculture also accounting for large segments of the economy.

James Gregory is a longtime professor of history at the University of Washington. He says that after the stock market crash in October 1929, it took between six months to a year to see a real impact on jobs in the Northwest.

And, because one of the hardest hit sectors right away in what became the Great Depression was home building, it wasn’t on some gleaming factory floor where the pain was first felt in Washington.

It was in the woods.

“The timber industry pretty largely shut down in the Northwest,” Professor Gregory said. “And it caused a real surge in unemployment, and then the ripple effect from the loss of those jobs and the loss of the purchasing that timber industry did in Seattle and elsewhere reduced employment and reduced business activities throughout the state.”

Professor Gregory describes the job losses over the next few years, from 1930 to 1933, as a “slow-moving avalanche.” Obviously, Gregory says, this was a very different pace than what we’ve seen the past two months during the pandemic.

In 1930, the first full year after the crash, unemployment in Washington reached as high as 9%. By the second year, it was around 17%. Then, by the third year – which was the election year of 1932 – the jobless rate in Washington likely reached as high as 25%.

And while that 25% is the rock-bottom out-of-work figure usually quoted in books and websites about the Great Depression, this number was the national average. The situation was even worse in the Evergreen State.

“We can’t really say with certainty, but there are indications that the unemployment rate in Washington state by 1932-1933 was higher than the national average … up to maybe 35%,” Professor Gregory said.

But that number, Professor Gregory says, “wasn’t as high as it was in some of the big manufacturing states – Ohio, Michigan – places where the key manufacturing industries had basically shut down entirely. Unemployment in some cities could reach 80% and 90% by 1932.”

One reason for the uncertainty is that unemployment numbers as we know them today weren’t tracked in the same manner. However, a book published by UW in 1944 – Social Trends in Seattle by Calvin F. Schmid – includes other indicators that took precipitous declines in Seattle in the early 1930s, including number of building permits issued, amount of bank deposits made, and assessed value of local real estate.

It might be a dumb question, but because the Northwest economy was less dependent on manufacturing than those other more industrial parts of the country – that is, if people here lived “lower on the hog” in a resource-extraction economy – was there less distance, economy-wise, for people to fall after the 1929 crash?

“It’s not a dumb question, but I would I would not agree,” Professor Gregory said. “For one thing, there’s no unemployment insurance in the 1930s and [most families] tended to be single-earner households [with a] typical male breadwinner, so when the husband lost his job the entire family income disappeared.”

And, whether a region’s economy is based on manufacturing or timber, these realities meant tough times everywhere.

“In those days, [you] lost a job and you pretty quickly became homeless, so it was a devastating impact on families,” Professor Gregory said.

The financial impacts included tenants defaulting on rent and homeowners defaulting on mortgages. Social impacts meant some households doubling up and moving in with relatives; and the growth of the homeless camps – called “Shacktowns” in those days – all over the city, including the big “Hooverville” near where the Starbucks building is now.

Civil and labor unrest also began to grow around this same time, when unemployment likely peaked in late 1932 and 1933, between the November 1932 election and March 1933 inauguration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

“By 1932 and 1933, there are more protests over unemployment,” Professor Gregory said. “There’s a massive movement called the ‘Unemployed Citizens League’ in Seattle, and other kinds of unemployed movements in other cities, but in Seattle and Washington, the Unemployed Citizens League had tens of thousands of members.”

The group, Professor Gregory says, “browbeat and persuaded city and state authorities to do more and more and more to try to provide relief services, some funds and some public works jobs for the vast number of unemployed.”

One thing that most historians, including Professor Gregory, agree on is that economic upheaval often creates dramatic change. In some parts of Europe in the 1930s, that meant the collapse of democracy and the rise of dictators.

In the United States, with FDR’s election in 1932, the most dramatic change was a package of legislation known as the New Deal – with massive federal investment in relief programs and work programs – and then, a few years later, creation of now-sacred government programs such as Social Security and unemployment insurance.

Thus, the suffering and strife of the Great Depression also helped create an enduring legacy. And Professor Gregory says that legacy is pretty much everywhere you turn in the Northwest.

“The federal government under the New Deal, in order to get people working, created massive infrastructure projects across the United States, and that infrastructure has been critical to the economic development of the nation ever since,” Professor Gregory said.

“All you have to do in our city is turn on a light or look out a window to see the legacies of the New Deal,” he continued. “The electrification of Washington, thanks to the building of the great dams on the Columbia – that’s a federal project, those are federal dollars, New Deal dollars, designed to do exactly what they did: Improve irrigation and bring cheap electricity. Half of the University of Washington buildings, the older ones, were built with federal dollars. Airports. The bridges, the I-90 bridge that we’re still traveling was built with federal dollars. Hundreds of smaller bridges. Highways. Lots and lots of buildings.”

Without those investments in the 1930s, Professor Gregory says, “we wouldn’t have had the infrastructure to be the world’s leading economy in the 70 [to] 80 years since.”

Even with the federal investments in those programs and that infrastructure, the American economy didn’t fully recover until the massive effort to ramp up for World War II. And this defense spending would contribute mightily to the rise of the Boeing-based economy that would lead the Seattle area until the tech boom of the 1990s.

And even with the tech boom and the Great Recession in recent memory, Professor Gregory acknowledges that these are unprecedented times.

There are elements of earlier crises – World War II, Great Depression, Cold War, the 1918 pandemic – that are present in the current struggle, but there’s no single event with this particular combination of massive job losses and a mixed (at best) federal response, along with a continuing viral threat to public health — and all of this with no clear end in sight.

With what he does know of past events, does Professor James Gregory have any predictions for what comes next?

“You know, I really don’t have any idea,” Professor Gregory said, with an uneasy laugh. “I wake up most mornings being very pessimistic about it all. And I can’t say, except it’ll be different.”

Speaking for myself, I do feel a general sense of hopefulness for a brighter future. It’s just hard to be very specific right now.

You can hear Feliks every Wednesday and Friday morning on Seattle’s Morning News and read more from him here. If you have a story idea, please email Feliks here.