Washington Territory’s race-based, discriminatory Chinese Police Tax

May 12, 2021, 9:52 AM | Updated: 12:05 pm

The violent expulsion of Chinese people from West Coast cities in the 1880s – including Seattle and Tacoma – is a dark chapter of Northwest history. But anti-Chinese discrimination in the Northwest can be traced back even further, to a law passed by the Washington Territorial Legislature in 1864.

A thesis about the evolving boundaries of counties in Washington Territory and the state of Washington published back in the 1920s (and reissued by the Yakima Valley Genealogical Society and Klickitat County Historical Society in 1979) mentions an 1864 law that created the race-based “Chinese Police Tax.” This law – and this tax – writes original author Newton Carl Abbott, was the reason that Spokane County had ceased to exist for several years beginning in the 1860s.

Abbott believes that in a gambit for more of the revenue from this tax – this was during the Civil War, when a drop in federal spending meant economic troubles in Washington Territory – Spokane County was administratively dismantled and its operations folded into Stevens County. Not surprisingly, this was the opposite of what Spokane County had intended. Spokane County, Abbott writes, wanted the revenue from the new tax, which targeted Chinese people – hundreds of whom happened to be working in adjacent Stevens County in the mining industry.

Mano-a-mano county battles aside, the early history of Chinese people in the western United States is not something we hear a lot about in the Pacific Northwest. The federal government’s Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 ended Chinese immigration here for 60 years, and those violent expulsions in the 1880s throughout the West reduced the physical numbers of the Chinese population, and contributed to their diminished role in the written histories of the region that were published in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Doug Chin is of Chinese ancestry, and he grew up in Seattle in something of a vacuum when it comes to local Chinese history. This absence of information inspired him, along with twin brother Art Chin, to author a number of books about Chinese history in Washington.

“I was born in Seattle a long time ago, in 1942,” Doug Chin told KIRO Radio earlier this week. “I went to school here in Seattle, and never read anything about Chinese. I only learned about anti-Chinese stuff when my brother started doing research on it.”

More than 50 years ago, Art Chin was a student at the University of Washington, doing research and writing term papers about Seattle’s Chinese history – much of which would be published in the 1970s in a typed, paperback, and now hard-to-find booklet called Uphill: The Settlement and Diffusion of the Chinese in Seattle, Washington. The publisher was the legendary and now long-gone Seattle used bookstore, Shorey’s.

“I read one of those term papers,” Doug Chin said. “That’s how I found out about the Chinese experience in Washington state.”

And what Doug Chin and his brother found out is that the first Chinese people had arrived in Washington Territory in the 1850s. While the infamous and now fairly well-documented Anti-Chinese Riots took place decades later, there was likely resentment and racial prejudice right away. The Chin brothers even mention the “Chinese Police Tax” on the first page of that first book published by Shorey’s.

That tax, Doug Chin says, was part of a pattern of discrimination.

In that era, the majority of white residents “see the Chinese as unfair labor competition, tools of the capitalists, as well as other cultural factors,” Doug Chin said.

Further, Doug Chin says, it was believed Chinese “couldn’t assimilate, they’re anti-religion, they were filthy, their intelligence was below the whites.”

“There was cultural, ethnic, as well as economic factors that people had against the Chinese,” he said.

Before Chinese people had arrived in Washington Territory, large numbers had come to California in the 1840s. And it was in California where they first faced the prejudice and discrimination that would eventually manifest along the entire West Coast, from California to British Columbia to Alaska.

It was in the Golden State where the legislature in April 1862 passed a law creating a race-based targeted tax. The transparent title of the legislation made no effort to conceal its intent, reading:

AN ACT TO PROTECT FREE WHITE LABOR AGAINST COMPETITION WITH CHINESE COOLIE LABOR, AND TO DISCOURAGE THE IMMIGRATION OF THE CHINESE INTO THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA.

The legislation’s title included the word “coolie,” a derogatory term for Chinese laborers in that era, and the law required all Chinese men and women 18 and older to pay $7.50 a quarter – what it called a “Chinese Police Tax.” This amounted to $30 annually, or the equivalent of about $500 today.

That same year – 1862 – Oregon lawmakers imposed a $5 annual tax on Black people, Chinese, those of mixed-race heritage, and Hawaiians; Oregonians had earlier voted to exclude free Black people as part of Oregon’s state constitution.

In 1864, Washington’s Territorial Legislature passed a law with almost exactly the same title as California’s: AN ACT TO PROTECT FREE WHITE LABOR AGAINST COMPETITION WITH CHINESE COOLIE LABOR, AND TO DISCOURAGE THE IMMIGRATION OF THE CHINESE INTO THIS TERRITORY. In fact, the territorial law in Washington is almost a verbatim copy of the California law, though there are some key differences.

In Washington Territory, the tax was $6 per quarter – which is much more than in Oregon, and a little less than in California. In each county here, the tax was to be collected by the sheriff, and the individual officer was allowed to keep a 25% cut of whatever he collected. The remainder was split between each county and the territory.

The premise and mechanics of enforcement seemed ripe for corruption, but there was official paperwork involved in the form of an official receipt created by the Territorial Treasurer and provided in quantity to each county. It’s not clear if any of those receipts survive; if they do, they would provide an unimaginable amount of insight into the effects of the Chinese Police Tax.

It’s also not clear how much enforcement – that is, collection of the tax – that there was, and how much it might have varied from county to county. A search of newspaper archives turned up one piece of evidence that the tax was being enforced in King County in 1866, with a notice from county commissioners that those Chinese people who didn’t pay could be forced to join a crew working to build a road.

One thing that does survive without any further evidence required is the race-based, discriminatory reality of the Chinese Police Tax; that’s clear, and clearly stated, right there in the enabling legislation’s title.

However, there is at least one unexplained oddity: The 1864 territorial law specified for Whatcom County a much higher tax rate of $10 per quarter, or nearly double of the rate in all other Washington Territory counties. That’s the equivalent of roughly $160 per quarter, or more than $600 a year in 2021.

Why would Whatcom County get to legally charge so much more than the other counties?

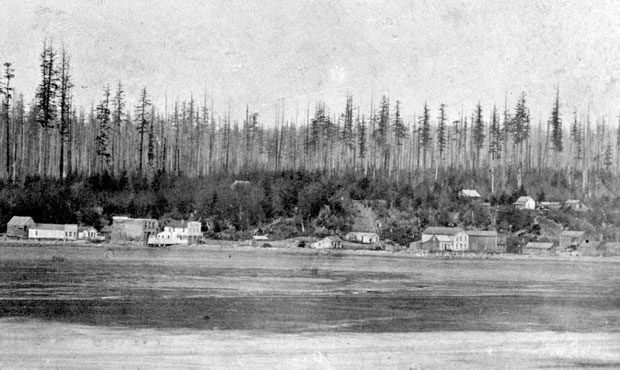

In 1864, Bellingham as we know it didn’t yet exist in Whatcom County. Jeff Jewell at the Whatcom Museum says there were two main communities there in what’s now Bellingham.

“You had Whatcom and Sehome as these rival two dusty towns, or rainy towns depending on what time of the year you wanted to look at them,” Jewell told KIRO Radio. “Each with maybe 750 to a thousand inhabitants, and serving almost strictly a San Francisco market, so everything was shipped out, coal and lumber.”

Jewell says there was a strong economic connection between Whatcom County and San Francisco, and maybe a cultural and political connection, too, that might have somehow influenced the Whatcom County exception in the 1864 law. That specific change in Whatcom County’s favor was likely advocated for by the members of the territorial legislature who represented the county: Frank Shaw or Henry C. Barkhousen.

Kelly Kunsch retired from Seattle University last year. He was an adjunct professor and reference librarian there, and studied Washington Territorial laws and lawmaking, and is an expert on the legal saga of Indigenous leader Leschi.

Kunsch and his former colleagues at the Seattle University Law Library enthusiastically pitched in with research help on this story, tracking down key documents, and uncovering an academic journal article positing that British Columbia officials were essentially mimicking California in the 1860s in the adoption of discriminatory laws designed to deprive Chinese people of rights and property. The article, entitled “THE PRESENT OF CALIFORNIA MAY PROVE . . . THE FUTURE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA,” appeared in the Spring 2019 edition of BC Studies.

Based on theories about what British Columbia lawmakers were doing, it’s not a great leap to speculate that Washington Territory’s legislature was doing the same in passing its own Chinese Police Tax, even down to copying the language nearly word for word.

But the much higher rate for only Whatcom County is still something of a mystery.

At Western Washington University in Bellingham, Dr. Josh Cerretti is an associate professor of history. The Chinese Police Tax wasn’t news to him, but he had never heard about Whatcom County’s higher rate. Dr. Cerretti theorized that it was related to Whatcom’s proximity to the international border, and the lack of any federal immigration policy in the 1860s.

“There were a number of people who would come to the states from China at that time, [who] were transiting through southern BC,” Dr. Cerretti told KIRO Radio. “And so they would come often from Hong Kong to Vancouver, and then from Vancouver, they might cross down by land, because there were often lots of opportunities [in Whatcom County] due to periodic labor shortages down here in the extraction industry.”

In the 1860s, Cerretti says, it was also far easier to travel by ship from China directly to British Columbia, rather than directly to an American port; Whatcom County, then, was the American soil nearest to where thousands of Chinese people first arrived in North America.

Oddly enough, California’s Chinese Police Tax didn’t last very long. The law was struck down as discriminatory by the California Supreme Court in 1862, the same year it was enacted. It took a little longer in Washington Territory and it didn’t involve the judicial branch, but the tax – and a similar, later tax targeting “Kanakas” or Hawaiians – was repealed by the territorial legislature in 1869. The 1869 legislation was called “AN ACT TO REPEAL ALL POLICE TAX LAWS DISCRIMINATING AGAINST CHINESE, MONGOLIANS AND KANAKAS.”

And, of course, even though it was repealed, and even though the language of the new law acknowledged that the old law was, in fact, “discriminating,” the Chinese Police Tax remains an inalterable part of the history of what’s now Washington.

As troubling as this episode of codified discrimination is, Doug Chin says that knowing this history is far better than it remaining obscured. This, Chin says, is where his true sense of belonging comes from.

“I think it’s important to know the legacy of the Chinese American experience in Washington state,” Doug Chin said. “Because if you’re Chinese, you want to feel that you contributed, or you belong here in Washington – that your race, the Chinese – played an important role in developing Washington state.”

“Otherwise you don’t feel part of it,” he said. “At best, you’re marginalized.”

Doug Chin is a member of volunteer group known as the Chinese Memorial Project. They’re working to commemorate the Anti-Chinese Riots with a monument to be dedicated on Alaskan Way between South Washington and South Main Street as early as next year.

You can hear Feliks every Wednesday and Friday morning on Seattle’s Morning News, read more from him here, and subscribe to The Resident Historian Podcast here. If you have a story idea, please email Feliks here.

Follow @https://twitter.com/feliksbanel