All Over The Map: Can you solve the mystery of Thanksgiving Island?

Nov 19, 2021, 9:23 AM | Updated: Nov 20, 2021, 8:15 am

Pretty much everyone has heard of Easter Island, with its distinctive sculptures, and Christmas Island, with its distinctive musical tribute from Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters. Both of those islands were named by European explorers centuries ago, who happened to arrive there on the respective namesake holidays.

So perhaps it’s not a great stretch to imagine that the same kind of circumstances might be the case for Thanksgiving Island right here in the Pacific Northwest.

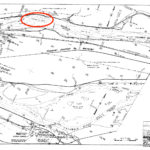

A topographic map – of the “Blalock Island” quadrangle – from 1908 offers scant details beyond Thanksgiving Island’s name and its location: nearer to the Washington side than to the Oregon side of the Columbia River, east of Goldendale in Klickitat County, and not far from the Benton County line. Upon closer inspection, a dotted line north of the island means that it’s actually part of Oregon, and within the boundaries of the Beaver State’s Morrow County.

Thanksgiving Island appears to be about a half-mile long and maybe a quarter-mile wide, somewhat crescent shaped, relatively flat, and comprising of a total of perhaps 200 acres.

Now, please don’t go rushing to the riverbank in Klickitat County or Morrow County to try to get a peek at Thanksgiving Island. You can’t see it, because it’s completely underwater.

When the John Day Dam was built by the Army Corps of Engineers beginning back in the 1950s, Thanksgiving Island was one of many islands that were ultimately inundated as water collected upriver from the structure. That stretch of water is known as John Day Reservoir or Lake Umatilla.

Along with islands, the reservoir also inundated Canoe Encampment Rapids, an area of turbulent water in the river which is believed to have been named by fur traders sometime in the first half of the 19th century. The dam’s waters also altered the topography, forcing residents to abandon their homes and move, and requiring that towns, highways, railroad tracks and power transmission lines be removed and relocated to above the high water level.

So, where does the name for the Columbia River’s Thanksgiving Island come from?

One hopes for a tantalizing story about a group of fur traders, settlers, or military men pulling ashore there on a blustery November day. A member of the party, writing in his journal as raindrops smudge the ink from his feather pen, realizes the day is a holiday. He excitedly shares the news with the rest of the group, and they work together to create an impromptu feast. The occasion is then memorialized forever through published accounts in newspapers and history books.

Unfortunately, a web search via Google and multiple newspaper archives turns up no such story.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) in Portland has maps showing the island before the waters rose, and spokesperson Tom Conning says the USACE acquired Thanksgiving Island from the Bureau of Land Management perhaps in the late 1950s. But they have nothing on the origins of the name.

Beyond the maps, little is known of the terrain or look of Thanksgiving Island or what, if any, structures or other improvements may have been built there during the settlement era, or if there were other cultural materials from the millennia before Europeans came.

“I couldn’t confirm whether we took anything off of it or anything like that,” Conning said. “But typically, when things are inundated by whatever pools that are created behind the dams, whatever wasn’t taken away … is still going to be there” under the water.

Lewis & Clark scholar David Nicandri, retired director of the Washington State Historical Society, says in an email that the origins of Thanksgiving Island are “indeed … mysterious.”

“The name certainly does not date to a Lewis & Clark usage,” Nicandri wrote. “They were in that vicinity, westbound, around 10/19-20, 1805. Clark notes passing a ‘bad rapid at the lower point of a small island’ on the 20th but more generally ‘the current much more uniform than yesterday’ (which ended at a camp near McNary Dam).”

“If I had to guess, I think the term might date from the fur trade era, HBC (Hudson’s Bay Company) etc.,” Nicandri wrote, referring to the first half of the 19th century, “or more likely the settlement period,” from roughly the 1840s onward.

The Assessment & Tax Department for Morrow County has in its possession at the county seat in Heppner, Oregon, an old map. A staff member there named Tracie Diehl wrote in an email, “I have looked at a 1935 Metsker map, but unfortunately it doesn’t label the owner of the island” – which means a dead end as far as tracing earlier ownership and possible leads on the name origins.

Jennifer Karson Engum is a historian who works at Tamástslikt Cultural Institute in Pendleton, Oregon, for the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation – which is home to Indigenous peoples whose traditional homelands encompass what’s now Thanksgiving Island. In 2015, Karson Engum co-authored one of the most ambitious Indigenous place name books ever published anywhere: “Cáw Pawá Láakni – They Are Not Forgotten: Sahaptian Place Names Atlas of the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla.”

“I recall wondering about that name myself a few times,” Karson Engum wrote. “It sounds like you have covered nearly all the bases.”

On page 82 of the Sahaptian atlas, Thanksgiving Island is mentioned – but only because there is a known Sahaptian Indigenous name for a fishing spot just across from Thanksgiving Island on the Washington side of the river.

With nearly all the other bases covered, the only person left to turn to is Mary MacArthur.

Beginning in the 1920s, MacArthur’s grandfather and then her father began compiling and publishing a comprehensive resource called “Oregon Geographic Names” (OGN). MacArthur is at work on the eighth edition, which will likely be published sometime in the next few years.

A quick look at editions one through seven of OGN confirms that Thanksgiving Island is not listed. But does Mary MacArthur have anything in the files she inherited from her father and grandfather?

No such luck.

“I would love to include it in the 8th edition if there is documentation,” MacArthur wrote, clearly demonstrating that, along with the files, she also inherited her forebears’ passion for serving as the “compiler” – the oddly appropriate title MacArthur’s grandfather adopted for describing his role in producing the family’s legendary books.

KIRO Radio listeners and MyNorthwest readers have come through with some pretty amazing research in the past, including when Matt McCauley solved the mystery of Kellogg Island in the Duwamish River.

Do you know the origins of the name of Thanksgiving Island, or are you willing and able to do some searching and sifting? If so, Mary MacArthur may be able to give you everlasting fame (without the fortune).

To sweeten the deal, I’ll personally throw in a free frozen turkey to the first person able to document the origins of Thanksgiving Island. Send your questions – and, hopefully, your answers – via my contact information below.

You can hear Feliks every Wednesday and Friday morning on Seattle’s Morning News, read more from him here, and subscribe to The Resident Historian Podcast here. If you have a story idea, please email Feliks here.