Long-lost Fort Tilton once stood guard over Snoqualmie Valley

Feb 6, 2019, 6:36 AM | Updated: 2:18 pm

Some of the most interesting facets of Northwest history are easy to forget about because they just aren’t around anymore. Or, in this particular case, the historic plaque marking where this landmark once stood just keeps washing away.

It was 163 years ago this week, in February 1856, when Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens instructed the territorial militia to build a series of defensive structures in the Snoqualmie Valley.

This was during what was called the “Indian War” or “Treaty War” of 1855 and 1856, when Stevens’ less-than-perfect treaty processes and the arrival of more and more settlers led to armed conflict between Natives and settlers around much of what is now Puget Sound and Eastern Washington.

RELATED: The Seattle General Strike of 1919

RELATED: The many times Eastern Washington has tried to secede

Cristy Lake is the assistant director of the Snoqualmie Valley Historical Museum. Lake grew up in the Snoqualmie Valley, and she told me that the first fort to be built, named Fort Tilton, was constructed sometime in late February or early March 1856.

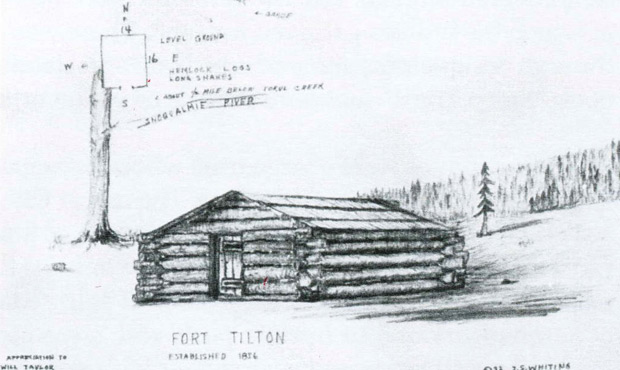

Fort Tilton’s location

The wooden fort was located a few miles below Snoqualmie Falls on the north bank of the river, along what’s now called Hatchery Road near the Washington State Fish Hatchery at Tokul Creek. Signs for the hatchery and Hatchery Road are hard to miss on the drive from Fall City up to the viewpoint at Snoqualmie Falls or Salish Lodge.

Documentation of the fort’s history, prepared in the 1970s, quotes historic sources that described the fort with a “corral for pack animals” around it, and that it “was built on a knoll at a bend in the river so anyone could be observed going up or down stream.”

As Lake tells it, Fort Tilton was a rudimentary affair.

“The way I would describe it, is it looks like a log house with no windows,” Lake said. “It was a very simple log structure about 14 feet by about 20 feet, with a reinforced door. It had a dirt floor. Its main purpose was to store supplies. The men would’ve been camped in tents around the area.”

This wasn’t a huge fort with room for hundreds or even dozens of men. It was essentially a reinforced storage structure for a tent camp that could double as a reinforced blockhouse in the event of attack.

Outposts in Snoqualmie Valley

Cristy Lake says Snoqualmie Pass was a strategic route over the mountains.

“The Cascade Mountains have only a few different passes that you can come through easily,” Lake said, and “Snoqualmie … is the lowest pass in the Cascade Range.”

During the Treaty War, civilian leaders and the military worried that Native Americans from Eastern Washington would cross over the Cascades to attack settlers on the west side.

“Because the people in Seattle feared that the Yakima were going to come over the pass and invade Seattle,” Lake said, “they felt that if they put some outposts along the Snoqualmie River that they would have enough advance warning to be able to stop that.”

The story is fairly complicated, with all kinds of social, cultural, military and economic factors that lie at the very heart of the continued struggles for reconciliation of how Native Americans were treated by settlers in the past, and how they should be treated now.

The leader of the Snoqualmies then was a man named Patkanim. Cristy Lake says that he had tried to organize an attack on settlers in the 1840s, but was unable to do so. By the time of the Treaty War, Patkanim had consolidated Native groups in the Snoqualmie Valley and had considerable power. Patkanim was generally considered to be non-hostile toward American settlers, and the Snoqualmies were viewed as potential allies against other Natives and tribes justifiably angered by the messy treaty process.

Patkanim

But some settlers weren’t so sure about Patkanim, Lake says, and this was also part of the reason for building Fort Tilton and an additional four more forts in the Snoqualmie Valley, near Snoqualmie Tribe settlements, in 1856.

“Some of the settlers really saw Patkanim as a friend to the US government, whereas others were very suspicious of him,” Lake said. “So, depending on which historic documents you read, you get very different versions, and so another reason for having the forts in the Snoqualmie Valley was locating US troops with weapons at [Patkanim’s] strategic villages to [keep an eye on him and] make sure that he didn’t actually join the uprising.”

“There was a fear that if the Snoqualmie Tribe joined an uprising that the US government wouldn’t be able to win,” Lake said.

Beyond several deadly skirmishes and attacks in the autumn of 1855 and the early weeks of 1856 (including the so-called “Battle of Seattle”), the Treaty War was pretty much over by the end of 1856. Afterwards, the militia was disbanded, and the Snoqualmie Valley forts were abandoned.

Lake says that some of the men who had been stationed at Fort Tilton in 1856 ended up staying in Snoqualmie Valley or coming back, forming a first significant wave of American settlement in the area.

“Several of them came back and actually took over some of the different fort buildings and used them as their early homestead,” Lake said. “And several of the men also [married women from] the Snoqualmie Tribe . . . one can imagine that perhaps they met their future wives on this [earlier] expedition, and then returned to farm and marry.”

Fort Tilton, where is it now?

Fort Tilton was still standing as late as the 1880s, according to some eyewitness accounts from a hundred years ago that Cristy Lake has read. Sometime after that, it collapsed and washed away, or perhaps its wood was repurposed.

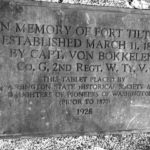

Lake also says that the Washington State Historical Society and Daughters of the Pioneers installed a bronze and stone (or perhaps concrete) marker at the site of Fort Tilton in the late 1920s, but it was washed away by a flood not long after. A wood marker installed in the 1970s was also eventually washed away, as was an interpretive panel that dates to the early 2000s.

Might the original bronze and stone marker still be nearby, perhaps beneath the rushing waters of the Snoqualmie River?

“I suspect that is highly likely,” Cristy Lake said. “It could even be still on site and just covered in a lot of silt.”

The actual site of the fort is on private property adjacent to a residence, but the roadside, where the markers used to be, is publicly accessible. There are no plans to do any kind of archaeological exploration there, and Lake says she knows of no effort to install a more permanent marker, because it would probably just wash away.

Naming Fort Tilton

Cristy Lake answered one more question about Fort Tilton: just who was that windowless and floorless log house named for?

“It was named for James Tilton , who [among other things] was the Surveyor General for . . . Washington [Territory], and he was also the officer above the person that was stationed at the fort that named it,” Lake said. “So he was naming it after his superior officer.”

So then, is Cristy Lake saying that the guy who named Fort Tilton was a suck-up?

“Oh, totally,” Lake said.

Editor’s Note: Special thanks to Ruth Pickering of the Fall City Historical Society for her assistance with this story.

More from Feliks Banel