Seattle police face constant rejection in efforts to help homeless

Feb 16, 2016, 9:19 PM | Updated: Feb 17, 2016, 1:52 pm

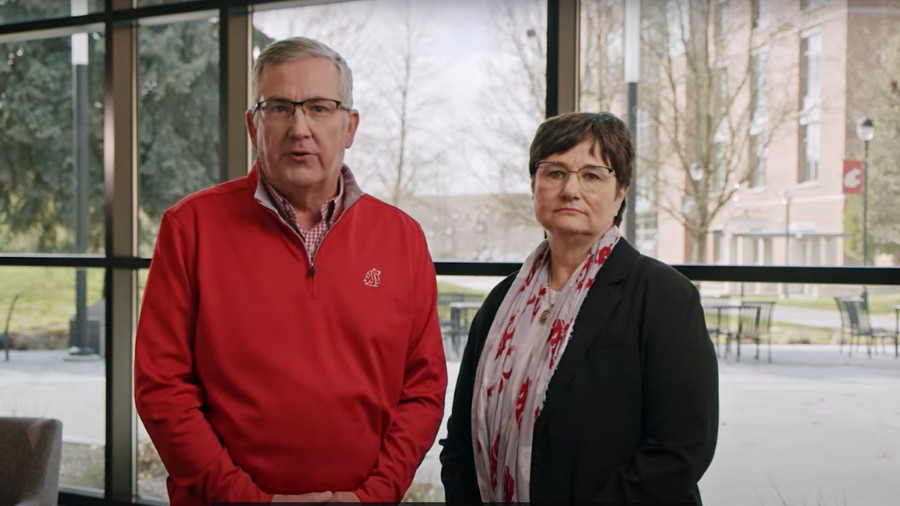

Seattle police Sgt. Paul Gracy offers help to a homeless man sleeping under the Alaskan Way Viaduct. (Josh Kerns/KIRO Radio)

(Josh Kerns/KIRO Radio)

As the city and everyone else continues seeking solutions to a homeless crisis, a small group of police officers is among those hitting the streets every day to offer help while also trying to keep Seattle safe.

Sergeant Paul Gracy’s day starts by checking emails to determine the source of the biggest complaints.

With just five officers, counting him, to handle community policing for the West precinct – which stretches from the Ship Canal to the stadiums, Lake Washington to Puget Sound – they have to pick and choose.

Related: Seattle will hire 200 more police officers

Our first stop takes us under a bridge between Fremont and Interbay, just below 15th Avenue NW.

Just beyond a fence along the train tracks we see where someone is calling home. They’ve built a makeshift structure out of a family-sized tent, tarps and building supplies.

Randall tells us he’s from Texas and has been on the streets of Seattle for several years. He has no job and is living on monthly Social Security checks. He gets food from the Ballard Food Bank.

Randall’s articulate. I ask him why he doesn’t go get a job.

“I get on the computer, I submit applications, but at the same time while I’m doing SSI (Social Security insurance) I can’t work,” he tells us. “While I’m fighting for my SSI still, if I’ve got a penny showing on my Social Security number, they’ll deny me again.”

And therein lies just one of the many conundrums Gracy encounters every day.

Randall is trespassing. But he’s out of harm’s way and sight. Gracy offers to connect him with services, but Randall insists he doesn’t need any.

“What’s my answer? What can I do for the gentleman? Most I can do is tell him to leave right now. And that will solve what?” Gracy said as we checked out a handful of tents clustered under the bridge along the Burlington Northern Santa Fe tracks.

Every encounter is cordial, with Gracy always asking how they’re doing, if there’s anything he can do for them, and what’s their plan.

He’s repeatedly rejected.

“What we’re doing is reaching out to them, exactly what the mayor is saying,” he said. “We’re trying to make contact with these folks, find out what services they need. But the real trick is getting them to accept that.”

As we head south, Gracy tells me to brace for the next stop.

We walk towards the Magnolia Bridge. Needles and piles of trash are strewn everywhere and the smell of urine permeates the air.

Rag-tag tents line the base of the bridge, overtaking the sidewalk. It’s nauseating and heartbreaking, reminding me of third-world slums.

This is one of the controversial unauthorized encampments the city has been criticized for clearing out. But ignoring it doesn’t seem like an option to Gracy either.

Related: How many cops does Seattle actually need?

“These folks will stay here until somebody comes in and says you can’t say here,” he said. “And this will not get better unless we come in and clean it. You stand there long enough and you’ll see the rats running through it. You don’t want somebody sleeping in that.”

Gracy refuses to give up. Sometimes he sees results, like his plan to coordinate all the derelict RVs strewn about Magnolia and Ballard, and move them to a temporary holding area in an industrial area behind the Seattle animal shelter.

“We have dumpsters down there, we have Sani-Cans down there for them,” he said. “We know where we can find them to get the service providers out to talk to them and address them. So I think that’s a positive. And I think that’s a win-win for everybody. I think that’s what it’s all about, trying to make life better for everybody if we can.”

One thing Gracy has determined over the years is simply giving shelter and food to the homeless isn’t enough. In getting to know so many people, he says the city needs to come up with a broad range of integrated services, essentially teaching all aspects of living life along with mental health and substance abuse treatment.

“Everyone needs a life coach,” he said. “And that’s kind of the human service providers’ job I would think rather than the police’s job. Hook up with these people, get to know them, and get them into something. We don’t have that now. That’s the problem.”

Our most disturbing stop takes us to a living hell beneath a bridge above the King County Jail downtown.

I’m reminded of a zombie movie as we work our way under the bridge. Some clearly high or drunk stagger around. Gracy checks to make sure those passed out aren’t dead, which happens all too frequently.

A clearly high young woman with drug-use sores all over her face pushes a stroller, seemingly oblivious to all that’s going on around her. Gracy checks to make sure there’s no child in it, which all too often he encounters under here.

Through it all, he remains cordial and friendly, offering help.

Again, not a single person accepts. Not even the fresh-faced 24-year-old woman who seems clearly out of place. She tells him she just got out of jail, but refuses his offer for a shelter because she prefers a place of her own.

“You know, what can I do? There’s only so much I can offer,” he says, clearly frustrated.

Despite his frequent frustration, though, Gracy says after 36 years, he’s not about to quit – even if it seems like every day he’s just making it up as he goes.

“I’m winging this,” he said. “How do I engage these folks? How do I get them to accept help when they don’t want it. What’s that magic word?”

On this day at least, the magic word is simply one of kindness. And one of these days he hopes someone comes up with some more concrete answers.

“I’m not giving up hope,” Gracy said. “I still love what I do, and even though it isn’t easy, I believe we’re making a difference.”

Sign up for breaking news alerts