All Over The Map: Forgotten plans for a canal between Olympia and Grays Harbor

Jul 27, 2020, 6:04 AM | Updated: 6:08 am

It was the Evergreen State’s transportation infrastructure project that took more than a hundred years to die.

And no, we don’t mean Sound Transit.

It was an idea that may have first been proposed as early as the administration of President Franklin Pierce in the 1850s, only to finally die during President Richard Nixon’s second term in the 1970s.

The Chinook Observer newspaper reported that future Confederate President Jefferson Davis, when he was Secretary of War in the Pierce administration in the 1850s, was supportive of the massive project.

Was the massive project a transcontinental railroad connection to Seattle?

Was it a safe and dependable route through the Cascades?

Or, perhaps a military road connecting Western Washington settlements?

It was none of these three projects — all of which eventually did happen, by the way. What Jefferson Davis, and a host of closer-to-home boosters supported, was a plan to build three canals to improve commercial shipping and connect the Columbia River directly to Puget Sound.

The vision called for two canals near the Southwest Washington coast. One would connect the Columbia River, at a point upriver from Astoria, to Willapa Bay, a distance of about 4.5 miles. A second canal would connect Willapa Bay to Grays Harbor, a distance of 10.5 miles.

But the granddaddy of them all was a 58-mile canal from Grays Harbor – via, at least partially, long stretches of the Chehalis River – all the way to Olympia at the south end of Puget Sound.

The idea came up multiple times in the 19th century, with backing from a series of visionaries and boosters possessing varying amounts of sophistication and influence, but none of whom was ever able to get the first shovel of dirt taken from the earth.

As odd as the idea to connect Puget Sound to the Columbia River might sound in 2020, it’s not as if the project was without benefits to early commercial mariners, who lacked much of the modern navigation technology and powerful engines that present-day seagoing professionals take for granted.

The canals would have created an inland route all the way from Portland to Southeast Alaska – because the southernmost canal would bypass the dreaded Columbia Bar, which still is one of the most treacherous stretches of Northwest waters. A canal route, protected from tides and currents, would take mariners from inside the Columbia Bar to Willapa Bay, then to Grays Harbor, and then on to Olympia. From there, Southeast Alaska is accessible via the Inside Passage. In the opposite direction, marine traffic could leave Puget Sound for southern ports via Grays Harbor, without having to first go north to exit via the sometime-blustery Strait of Juan de Fuca.

While treacherous waters could be avoided, it’s unclear if the canals would’ve been a significant time-saver. One configuration of the Olympia-to-Grays Harbor canal included as many as nine locks, along with numerous drawbridges for automobiles and other land-based traffic.

After another boost of enthusiasm in the 1890s, the idea came up again a few times in the teens, around the time that the Panama Canal was completed. In 1913, the Washington State Legislature formally

“memorialized” the United States Congress to examine the scheme.

In reporting the legislature’s request-making of their federal counterparts, The Seattle Times quoted long-serving State Senator Oliver Hall from Colfax in Whitman County.

Senator Hall, it seems, had a sense of humor, along with a willingness to vote “yes.”

“Before he voted for the memorial,” The Times wrote, “Senator Hall facetiously remarked that he would like to have it referred to a committee so that it could be amended to include appropriation to run the Columbia River through Snoqualmie Pass.”

Jokes – and “yes” votes – aside, the feds either said no or ignored the request from Washington’s legislators. The result was the same: no canals.

But, 20 years later, a few important political and economic realities had changed, and the plan was taken more seriously than it ever had been before. It was early 1933, and the United States, along with the rest of the world, was struggling with massive job losses and a stalled economy in the depths of the Great Depression. If that weren’t enough, the world seemed, to some keen observers, to be headed once again toward war.

Washington’s canals were shovel-ready, to put it mildly, so the legislature passed a bill and Governor Clarence Martin signed it into law in March 1933, around the same time that “New Deal” President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was inaugurated for his first term. The law directed funds from state taxpayers to create the grandly named Canal Commission of the State of Washington to examine canal feasibility and report back to Governor Martin.

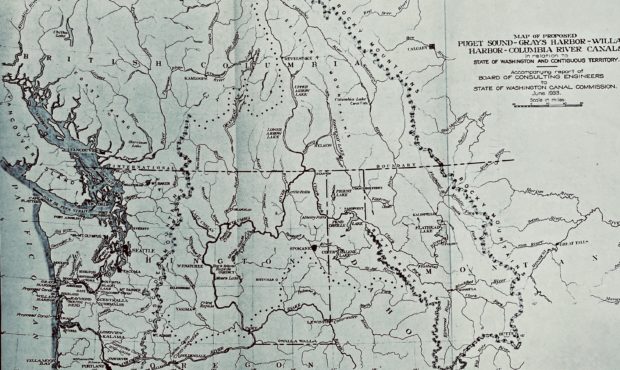

Within a few months, the Canal Commission issued its report. The compact hardback volume, replete with gold-leaf title lettering on its bright blue cover – “Report on Proposed Canals Connecting Puget Sound-Grays Harbor-Willapa Bay-Columbia River” – laid out the best canal routes, and the associated costs and the benefits. Along with charts, graphs, and all kinds of data – as well as foldout maps – the report laid out projected safety and efficiency improvements for commercial shipping and recreational boaters, as well as helpful factoids, such as how a canal would be superior to a highway for moving troops from Fort Lewis to the coast – should those jittery early 1930s turn into some kind of all-out war. The canals — between 90 and 120 feet wide, and deep enough for most big ships of that era – would also be a terrific way to move all that raw timber and other natural resources by ship rather than road or railroad. Annual operating costs, the plan said, would be covered by tolls.

As a jobs program, the $25 million cost of the Olympia-to-Grays Harbor alone would’ve put thousands to work and pumped the 2020 equivalent of almost half-a-billion dollars into the state economy at a time when it would’ve made a huge impact. By any estimate, it would’ve taken a lot of shovels – in the calloused hands of a lot of shovelers and other equipment operators – to move an estimated 155 million cubic yards of dirt. It was “Infrastructure Week” on steroids.

The hard-bound and lavishly presented 1933 edition of the canal idea kicked around for a year or so. Then, in 1934, the Army Corps of Engineers chose to not approve it, according to The Seattle Times, because it was “not economically justified.” That the project – and its thousands of jobs – could not get public funding or enough public support to happen during the Great Depression says something about its overall feasibility that a reading of the old newspaper archives doesn’t quite tease out.

This uniquely Northwest version of “a man-a plan-a canal” came up again in 1941 when Representative Martin Smith of Hoquiam, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives who served on the House Rivers and Harbors Committee, got the other committee members to agree to explore the concept based on its value to national defense. It’s unclear if this exploration ever took place, but again, the canal concept was dead in the slack water. By the end of 1941, the United States had entered World War II. If troops from Fort Lewis needed to reach the coast, they probably went via truck.

Some 20 years later, in the early 1960s, the state legislature funded additional review of the old plans, as well as a new idea: to connect the lower end of Hood Canal to Puget Sound via a 2-mile canal. In 1967, the Army Corp of Engineers said the Willapa Bay to Grays Harbor portion of the original proposal had “merit,” but merit was about all the plan was ever able to muster.

By the early 1970s, the Canal Commission had run out of funding yet again, and the canal idea dried up for good.

You can hear Feliks every Wednesday and Friday morning on Seattle’s Morning News and read more from him here. If you have a story idea, please email Feliks here.