Affordability and demand: A recipe for a shortage of Seattle cooks

Jan 11, 2019, 5:47 AM

First, fill your city with more and more restaurants, then add a dash of an affordability crisis, spread your cooks thin, and allow that to simmer for a few years — what you get is a considerable shortage of Seattle cooks.

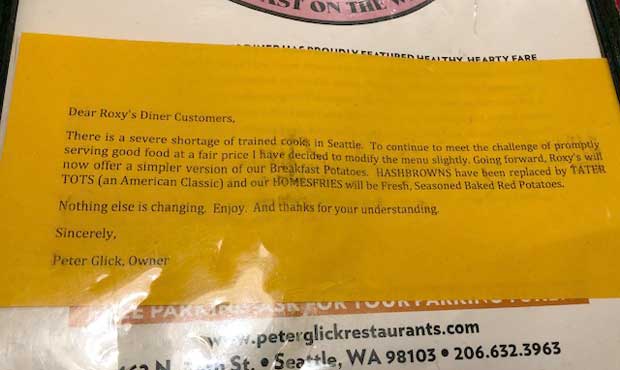

Take Roxy’s Diner, for example. The restaurant often has a line out the door with patrons eager for East Coast flavor. But those patrons were recently greeted with a note on the menu.

RELATED: Blue C Sushi abruptly closes its doors

RELATED: If you can’t live in Seattle, why not move?

Citing a “severe shortage of trained cooks in Seattle,” Roxy’s has resorted to modifying its menu to offer “simpler” versions of its potato dishes. It’s not clear how long the message has been posted on the diner’s menus. MyNorthwest reached out to the owner of Roxy’s for a comment, but have yet to receive a response.

The sentiment is no surprise to Seattle’s restaurant community, however.

“There are just not enough new cooks coming into the city, or who can afford to live in the city,” Jennifer Engles-Klann said. “And couple that with the number of restaurants that have opened, it just creates a massive shortage.”

Engles-Klann is director of operations for the Derschang Group, which owns a range of Seattle hot spots, such as Linda’s Tavern, Oddfellows, Queen City, and King’s Hardware. She also serves on the government affairs committee for the Seattle Restaurant Alliance.

Word that Seattle cooks are spread thin has been going around town for a few years. In 2017, the Evergrey reported that the city had 2,500 restaurants, which was 500 more than a decade before that. At the time, King County restaurants needed 3,955 prep and serving staff — the supply was only 634. Engles-Klann notes that the gap has only grown wider.

By the end of 2017, there were 290 restaurants and bars that opened in Seattle just that year, versus 85 closings. The Seattle Times reports that 362 restaurants opened in 2018, with only 71 closures.

“That’s a lot of cooks who have to come from somewhere,” Engles-Klann said. “I think that’s the biggest challenge. There are a lot of places that need a lot of cooks and there just aren’t enough of them in the city to go around.”

“If you took that and said ‘there’s 362 new clinics open,’ 362 new doctors would sound like a huge number, and when you think about the fact you need two or three or four cooks to open a kitchen, that’s a big pool of people to try to find in Seattle,” she said. “… It’s amazing, and an awesome environment to be in, but it does make the cook shortage a little more glaring.”

Why Seattle cooks are scarce

Other anecdotal evidence in the Seattle Met points a possible finger at the growing recreational marijuana industry, drawing cooks away from the kitchen to regular 9-5 jobs at similar pay.

“Anecdotally, in our stores, we’ve hired someone and they work for about a week, and they realize they live in Bothell and the last bus leaves at midnight and their shift goes until 1 a.m. It’s not feasible for them to stay working for us,” Engles-Klann said.

Engles-Klann said that some Seattle cooks who work at her restaurants also have two or three other jobs around Seattle — partially because there is a need, and partially because they need the work to stay afloat in the city.

“It is really hard for someone, a line cook or a dishwasher, someone in the back of house, to afford to live near the restaurants (they work in), Capitol Hill, downtown Seattle, Belltown,” she said. “It’s hard for them to live in that housing market without two or three jobs … or share a house with six or seven other people, which is what a few of our staff do. They have a lot of roommates.”

As for minimum wage, every time it goes up, it impacts the front-of-house wages, which then bumps up the kitchen wages, Engles-Klann said. Managers then do a little math to make ends meet. That can affect hiring and it also affects menu prices.

It also impacts the competition between restaurants, each trying to attract and maintain chefs.

“The fact that there are large employers and smaller employers mean that it forces small employers to keep up with the large employers, because we are pulling from the same pool of staff,” Engles-Klann said. “So if Tom Douglas raises his hiring wage, we have to, too, just to try to keep up.”