Kingdome a symbol of a new era in Seattle

Mar 26, 2015, 6:24 AM | Updated: 10:58 am

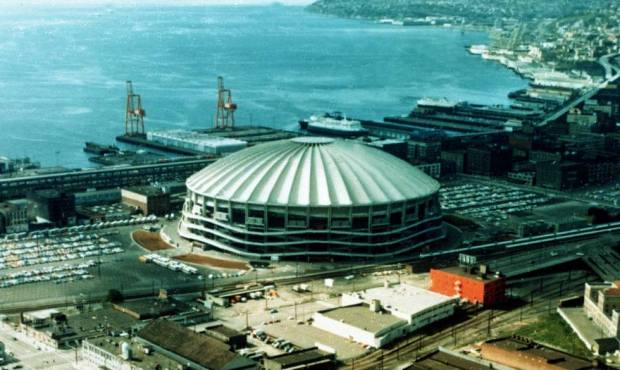

When it was first envisioned and before it was even named, the Kingdome was destined to be the pride of the city, says local historian Feliks Banel. (AP)

(AP)

On a quiet Sunday morning 15 years ago, a hallowed place of local history was reduced to rubble in seconds. Tens of thousands of people gathered to watch on March 26, 2000 as the Kingdome was imploded to make way for CenturyLink Field.

The Kingdome was described by some critics as representing the worst of brutalist modern architecture. But who cares what some critics say? The Dome was also the original home of Seattle’s NFL heroes, and where legendary KIRO Radio broadcaster Pete Gross invented one of this region’s first catchphrases “Touchdown Seahawks!” for the duo of quarterback Jim Zorn and wide receiver Steve Largent.

Related: Kingdome, Safeco Field featured in throwback tweet from the Mariners

It was an indoor field of synthetic dreams where the 1995 Mariners won the hearts of a skeptical city, and where Dave Niehaus cried “I don’t believe it!” when Edgar Martinez hit “The Double” and the M’s beat the Yankees in Game 5 of the ALDS. It was the place that rocked and rolled during an earthquake in 1996 that sent Niehaus and thousands of Mariners’ fans headed for the exits.

It was also homecourt for the World Champion Seattle SuperSonics, where Bob “Voice of the Sonics” Blackburn called the swishes and full-court press of Downtown Freddy Brown, Gus Williams, Jack Sikma and their other distinguished NBA teammates. It was a heckuva great place to get out of the January rain and cold and check out the latest nautical gear at the Big Seattle Boat Show.

When it was first envisioned and before it was even named, the Kingdome was destined to be the pride of the city, the symbol of a new era, and a huge public investment in the region’s future.

In 1968, as part of the series of bond measures called Forward Thrust, voters approved funds to build a stadium with the hope of attracting major league sports to Seattle.

When the ballot measure for the stadium passed, Major League Baseball awarded a franchise to Seattle, and the Pilots played here for the 1969 season in temporary digs in the Rainier Valley. It was the Pilots’ one and only season, but they would’ve ultimately played in the Kingdome. Instead, the hapless team was sold and became the Milwaukee Brewers. King County sued MLB and was awarded the Mariners franchise.

The people who wrangle over these sorts of things looked at Seattle Center, the waterfront and other potential locations before they chose land south of Pioneer Square. They decided to build a concrete multipurpose domed stadium, which was practical for the variety of activities it could host, and for the year-round protection it offered from the weather around here.

Once ground was broken, it took five years to construct, but the Kingdome — named after its home county in the years before public facilities took on naming sponsors — finally opened with great fanfare on March 27, 1976. Big events in those early years included a Billy Graham Crusade, a sold-out rock concert by Paul McCartney and Wings, and the Chief Seattle Council Boy Scout Jamboree.

In spite of the gas crunch, inflation and other global economic troubles of that era, the late 1970s were heady times in Seattle. The Seahawks played their inaugural game in the Kingdome in August 1976, and the Mariners threw out their first pitch the following spring. Then the Sonics moved in, and so did the original Sounders of the old North American Soccer League.

It was an exciting era in the city’s history and it was all happening at the Dome. But then came the 1980s. Even though all the pieces seemed to be in place, a few key ingredients were missing. One was a consistently winning team.

The Seahawks reached the NFL playoffs for the first time in 1983, beating Denver in the Dome on Christmas Eve to win the Western Conference; beating Miami at Miami on New Year’s Eve, and the losing the AFC Championship to Oakland on January 8, 1984. Other than that bright spot, Seattle’s pro teams had some of their worst years in the 1980s.

After their 1979 championship, the Sonics flopped and eventually moved back to Seattle Center Coliseum (later renamed KeyArena). The original Sounders went out of business, along with the rest of the North American Soccer League. The Mariners struggled and ticket sales collapsed.

In 1994, two roof tiles fell inside the Dome before a Mariners game, shutting down the place for weeks and sending the team on an interminable road trip. Then, two workers later died while making repairs.

What some say really doomed the Dome was the lack of luxury suites and rise of modern reboots of classically-styled baseball parks. Franchise owners in other cities began creating high-priced private seating areas in new facilities. These exclusive viewing boxes were fast becoming a key part of many big league teams’ revenue packages. Seattle teams wanted in on the luxury suite action, too, but the Kingdome just couldn’t deliver.

The Kingdome’s spartan look and feel was not aging well; add to this the raves for the new home for the Baltimore Orioles, Camden Yards, that invoked the best of vintage ballparks and included all the modern amenities and revenue generators. The sun was beginning to set on the once mighty Dome.

Various owners threatened to sell the Mariners and/or move them to another city, until finally, the current ownership group assumed control and adopted the ’95 slogan “Refuse to Lose.” It successfully maneuvered a public financing package through the Legislature to build a new baseball-only stadium.

Paul Allen bought the Seahawks from Ken Behring, and the football team began its own successful stadium campaign that culminated in an election paid for by Allen’s organization.

The Mariners moved to their new retractable roof field-of-dreams at Safeco Field in July 1999. That same year, construction began on what’s now called CenturyLink Field for the Seahawks and the new Sounders. Before too long, what was once the centerpiece of Seattle’s rising sports dynasty — the Kingdome — now stood empty and in the way of the major sections of CenturyLink. But not for long.

The stadium that was nearly a decade in the making imploded in seconds just one day shy of its 24th birthday. The blast kicked up one of the biggest clouds of dust in the city’s history. Even though the debris was cleared away in a matter of weeks, for many who attended an event at the Dome, 24 years of Seattle memories remain piled up on the former site – and on the region’s consciousness – like so many tons of invisible broken concrete.

There’s not much to see of the old Dome down in Pioneer Square these days. But if you listen carefully down in the concrete canyons between CenturyLink and Safeco where unnatural urban breezes kick up cyclones of peanut shells and the torn pages of scorecards, you might still hear Dave Niehaus calling “The Double,” over and over again.