All Over The Map: The Mystery of the Phantom Canal

Jun 3, 2022, 8:42 AM | Updated: Oct 25, 2022, 4:20 pm

More than 120 years ago – long before the Ballard Locks changed the shape of Seattle’s future – an ambitious entrepreneur dug a canal from Elliott Bay to Beacon Hill in an attempt to connect Puget Sound and Lake Washington . . . or DID he?!?!

Cue the “Unsolved Mysteries” music and alert Robert Stack to get his fedora and overcoat ready, and check your nearest public library to see if they have a copy of “The Hardy Boys and The Mystery of the Phantom Canal.” If there is such a book, it was probably set in Seattle.

Everybody knows that the Ballard Locks, Lake Washington Ship Canal, and Montlake Cut together connect saltwater Puget Sound to freshwater Lake Washington, and have since 1917. But, that canal and that specific route were not always a foregone conclusion.

If you go back to the 1890s, an entrepreneur and former Territorial Governor named Eugene Semple advocated for another route via the shortest distance between saltwater and freshwater: from Elliott Bay across Beacon Hill to Lake Washington.

If cutting a canal through Beacon Hill sounds crazy – you’re right, it is crazy – and the guy who can help us all understand what it might have looked like is David B. Williams.

Williams is an expert on Seattle topography and author or co-author of several books – including “Too High & Too Steep. ”

A canal cut or dug through Beacon Hill wouldn’t be some skinny sort of man-made Hell’s Canyon. According to David B. Williams, it would perhaps be reminiscent of the natural topography in another well-known part of Seattle.

Beacon Hill sliced through by a canal would be “sort of similar magnitude as the space between Queen Anne and Magnolia-Interbay,” Williams told KIRO Newsradio earlier this week. “It would have been narrower, but if you could just push those two hills a little bit closer together, that’s what a canal would be like” in that part of South Seattle.

Before they started work on cutting through Beacon Hill, Eugene Semple’s workers used dredges to create the East and West Waterways of the Duwamish River, and they used the dredged up dirt to create dry land on Harbor Island and the areas on what had been the east bank of the river. Previously – for millennia – the natural state of the Duwamish at Elliott Bay had been that of a muddy and sprawling river delta, influenced by river flow and tides, and of a very different look and feel than how it is now.

And, this may sound obvious, but we know that the East Waterway and West Waterway were built because they’re shown on old maps from the early 20th century, and because they’re still there if we go and look today.

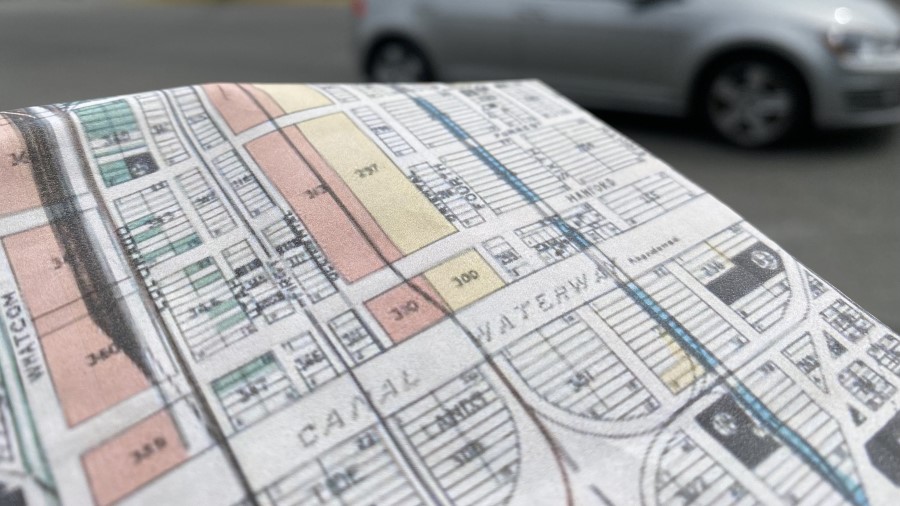

And it’s old maps that are at the heart of the “Mystery of the Phantom Canal.” There are several examples of maps from the early 20th century that show a good-sized canal running east from the East Waterway. This is the so-called South Canal that Eugene Semple promoted as a better way to connect Elliott Bay to Lake Washington before the US Army Corps of Engineers settled on the route we all know today.

The weird thing is that these old maps don’t say “proposed canal” or “planned route of canal,” they show an actual canal stretching from the East Waterway at least part of the distance to the base of Beacon Hill. And, to further confuse things, along with the maps, there are also newspaper stories from the archives from around the same time that read as if an actual canal – not just a route – existed.

Visiting the area in person where the putative canal may once have existed, there’s no obvious indications of a deep trench having been filled in, no “ghost signs” or businesses with helpful vestigial names, such as “The Canal Tavern” or “Semple Hotel.” The only evidence I could find are two parallel east-west streets – Horton and Hinds – which David B. Williams says are closer together than other nearby streets. Since the gap between Horton and Hinds doesn’t match up with the rest of the grid – and based on those old maps – Williams’ theory is that the location of those streets may indicate the boundaries of the old canal, or at least the location of the land that may have been set aside for the canal.

As it turns out, we may never know what really happened, or what really existed in that narrow corridor south of downtown.

“There’s so much we don’t know,” Williams said. “In particular, you read those newspaper articles and they make it sound like there’s a canal there. But where are the photos? And I could never find any engineering drawings – you’d think there would have been some sort of engineering drawings.”

“I could never find any anywhere,” Williams said.

One possible theory is that the whole thing was a scam – some kind of real estate speculation or other way of securing investors, or just upping the value of real estate in proximity to the route of the canal – much the way a proposed rail route would raise the value of land in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

While the flatlands part of the canal is a mystery, Williams says that Semple’s workers actually did make progress on a section of the proposed canal on the west side of Beacon Hill. Thus, while there’s no evidence of the South Canal near the East Waterway, Semple and his workers can actually claim credit for taking a massive chunk of dirt out of the side of Beacon Hill. They used water to sluice it onto conveyor belts to use as fill dirt closer to Elliott Bay – to convert tidal lands into usable real estate.

Anyone who’s ever driven south on I-5 and taken the exit for Beacon Hill to South Columbian Way has actually traveled part of the route of the South Canal. That notch in the hillside – where the I-5, Spokane Street, and South Columbian Way interchange — was built in the 1960s and took advantage of the dirt removal Eugene Semple had overseen a half-century earlier.

The next time you take that exit, don’t think of it as merely a trip to Beacon Hill. Think of it as a historical expedition through the only remaining evidence of the “Mystery of the Phantom Canal,” and a glimpse into a portal to an alternate past.

But just don’t expect to run into the Hardy Boys or even Robert Stack.

You can hear Feliks every Wednesday and Friday morning on Seattle’s Morning News and read more from him here. If you have a story idea, please email Feliks here.

Follow @https://twitter.com/feliksbanel