According to Letko, the discovery of Khosta-2 highlights the need to develop universal vaccines for sarbecoviruses in general, rather than just known variants of COVID-19.

“Unfortunately, many of our current vaccines are designed for specific viruses we know infect human cells or those that seem to pose the biggest risk to infect us. But that is a list that’s ever-changing,” Letko said. “We need to broaden the design of these vaccines to protect against all sarbecoviruses.”

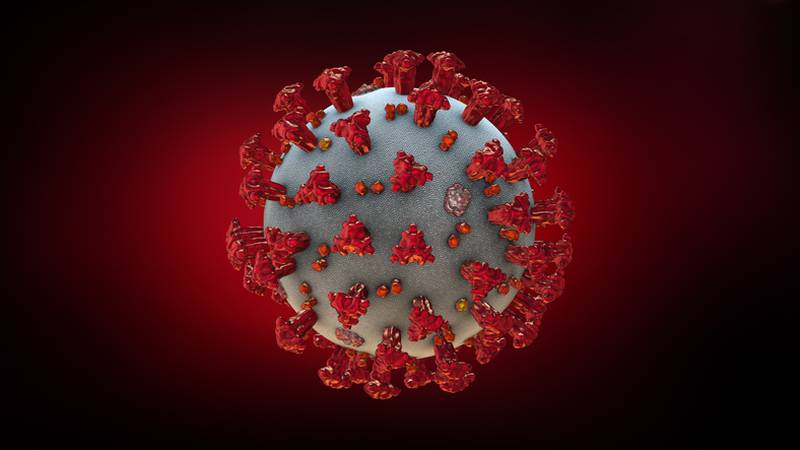

When the Khosta-1 and Khosta-2 viruses were originally discovered in Russian bats in late 2020, it was thought that they posed no threat to humans. But researchers learned that, like SARS-CoV-2, Khosta-2 can use its spike protein to infect cells by attaching to a receptor protein found throughout human cells.

Then, using a serum made from people vaccinated against COVID-19, the researchers saw that Khosta-2 was not neutralized by the vaccines.

Letko did say that the virus lacks some of the genes that are believed to be involved in pathogenesis in humans, but that there is a risk of it recombining with a virus like SARS-CoV-2.

“When you see SARS-2 has this ability to spill back from humans and into wildlife, and then there are other viruses like Khosta-2 waiting in those animals with these properties we really don’t want them to have, it sets up this scenario where you keep rolling the dice until they combine to make a potentially riskier virus,” Letko said.