The worst atmospheric river of all was winter 1861-1862

Jan 12, 2023, 8:25 AM | Updated: 9:59 am

An atmospheric river moving across Western Washington is causing high avalanche danger in parts of the Cascades. But even with buckets of rain dumping on a city already famous for its dreary raininess, for the really stormy stuff, you have to go back to the winter of 1861-1862.

Weather history, especially accounts of extreme weather, is pretty well known around here, and some accounts go back about 140 years. The Columbus Day Storm of October 1962; the Blizzard of February 1916; and even the Big Snow of 1880 were documented by journalists and photographers. Official weather records were kept in Seattle beginning in the 1890s, but before that (with a few exceptions), anyone looking to understand the history of local weather is forced to rely on personal letters and diary entries, as well as surviving newspaper accounts.

That’s why Larry Schick, longtime KING 5 weatherman who later became a scientist for the Army Corps of Engineers, was pretty excited recently when he made a discovery that filled in some of the blanks in research he’s doing for a book he’s writing about the winter of 1861-1862.

“I was totally thrilled,” Schick said earlier this month in Seattle. “I had looked all over Washington. Nobody had it here – Weather Service, UW – nobody had it. But I knew it existed because I saw it referenced.”

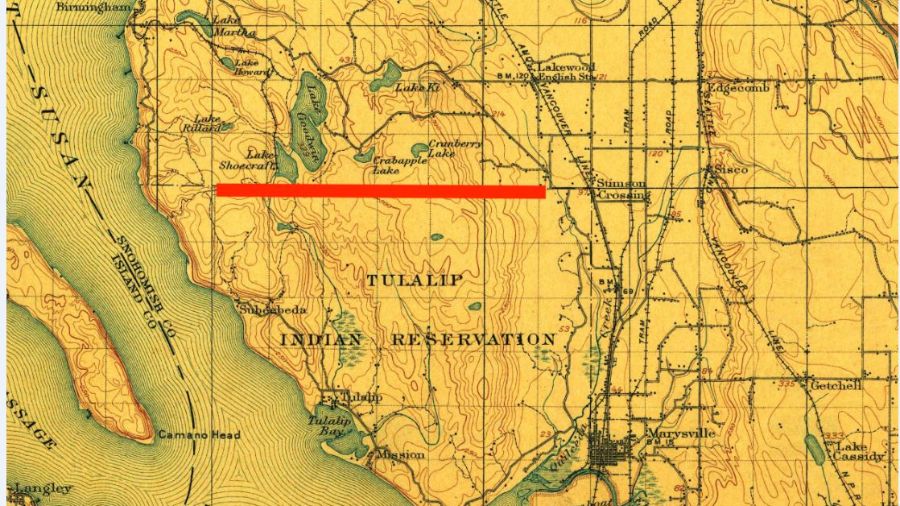

All Over The Map: Marysville named for a cannibal?

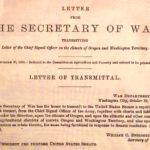

The “it” that Schick had found – at UC Berkeley – was a report from the Secretary of War published in 1888. In this report were detailed weather observations from US Army forts all over the Northwest going back as early as the 1840s.

Schick had read a lot of anecdotal information about that monumental winter, but he hadn’t seen a lot of data, which, as a scientist, is something that Schick relies on. The data in the 1888 report wasn’t collected by meteorologists, Schick says, but by Army surgeons. This was back when the weather was considered to have a direct relation to health.

And what made data from that winter of 1861-1862 so worth chasing down and worth getting so excited about?

“After doing 20 years of television in Seattle, I got a job with the Army Corps of Engineers in water management, and I was in flood control there and extreme weather conditions. We studied severe storms, and I was the West Coast expert from Washington, Oregon, and California,” Schick said. “When I’d read reports on storminess, not only in the Pacific Northwest but in California, they would report on some big storm during the 20th century, but they’d always refer back. [They’d say] ‘This was really bad, but it wasn’t quite as bad as 1861-62.’ [The author of the report] wouldn’t tell me any more . . . and I was like, ‘Wow, everybody always refers to that, it’s the benchmark.’”

All those mentions without additional details piqued Schick’s interest and led him to search high and low for anything related to the winter of 1861-1862 that he could get his hands on, and led him to begin work on a book about the topic.

Schick says the winter of 1861-1862 is notable because it’s comprised of a series of extreme weather events over a roughly two-month period from late November 1861 to early February 1862.

“People here saw some of the biggest storminess along the West Coast – really, from Washington, Oregon, and California – that really we’ve ever seen,” Schick said. “It’s not that we haven’t seen bigger storms or maybe even deeper cold, but the consistency of it was so huge, and the peak flows of the rivers, especially in Oregon and California, were like something we have not seen before. The cold was incredible here in the Pacific Northwest, but it was a progression of things that happened over about eight weeks.”

Schick says the intense flooding was mostly in Southern Oregon and Northern California; here in Washington Territory (which, until 1863, included all of present-day Idaho), it was mostly about snow and extreme cold.

Washington mountains named for forgotten giants of journalism

The data Schick found in the 1888 report revealed some interesting extremes in cold temperatures.

“So, Seattle during that time, I got a variety of temperatures. I had a Woodland Park …. temperature of four below zero. Downtown Seattle was about two below zero, and the modern record is zero at Sea-Tac,” Schick said. “East of the mountains, [it was] much colder, and the cold lasted a long time. I had 29 degrees below zero in Walla Walla, [and] 34 degrees below zero in [what’s now] Florence, Idaho.”

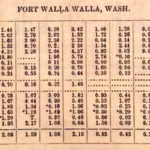

Schick also found precipitation data that illustrate the unbelievable amount of rainfall during the winter of 1861-1862. For example, in precipitation records for Fort Walla Walla, rainfall in December 1860 was 2.84 inches, then, in December 1861, it was 12.84 inches or more than four times the amount of the previous December. In January 1861, 4.94 inches fell; in January 1862, the rainfall total was 11.63 inches, or nearly three times more than the previous January.

In all those numbers, Schick also spotted one wintertime pattern very familiar to Puget Sound residents.

“I could pick out these atmospheric rivers, these ‘Pineapple Express’ warm and wet patterns that really cause most of our flooding,” Schick said. “I could pick those out really easy, and it was easy to pick one out in Vancouver, Washington, in early December of 1861 — no, if, and or buts about it.”

How could a 21st-century forecaster discern a “Pineapple Express” from 154 years ago?

“It was 59 degrees in the morning [in] early December,” Schick said, almost giddy as he recalled the discovery. “It’s never that warm. There’s only one thing that can do that, and that’s an atmospheric river — what we call ‘Pineapple Express’ — these warm and very wet Hawaiian storms that give us our biggest rains and our flooding in the Pacific Northwest.”

Schick says a check of the newspaper archives proved his hypothesis.

“Sure enough, the [1861 Vancouver area] papers [said] ‘Big Floods’ the next two days, ‘Huge flood, we’ve never seen anything like it.’”

In addition to newspapers, other written records that shine some light on the winter of 1861-1862 include numerous regional history books published around the turn of the 20th century, when that harsh season was still in the living memory of many.

The year 1861 was momentous in American history with the beginning of the Civil War. In the Pacific Northwest, non-Native settlement had been underway in earnest only for a few decades; by the 1860 US Census, Oregon had become a state and had more than 50,000 residents, while the non-Native population of Washington Territory was less than 12,000.

Still, records were being kept, and books about recent history were being published.

In “An Illustrated History of Klickitat, Yakima and Kittitas Counties,” published in 1904 by the Interstate Publishing Company, the unidentified author wrote:

That winter is known in local history as the severest ever experienced by white men in the Northwest, and the Yakima country was not more favored than were other parts. On the 10th of November, Mr. Thorp informs us, snow began falling, and it did not cease until it had attained a depth of eight inches. This settled down to four inches of hard, icy snow, upon which came successive falls until by December 20th, the earth had a compact blanket two feet thick. Throughout the whole of the 22nd and the succeeding night, rain came down in torrents, settling the snow to a depth of eighteen inches. A hard frost on the night of the 23rd converted this into a vast sheet of ice, the last of which did not disappear from the face of the country until after the middle of the following March. There was no thermometer in the valley at the time, but some idea of the cold may be obtained from the fact that the Yakima and Naches rivers very early froze to the bottom, swift mountain streams though they were.

Historian Clarence Bagley wrote in 1916 of the Winter of 1861-1862, in his three-volume “History of Seattle”:

“Fruit trees were killed in many orchards, and large numbers of livestock died from the severity of the weather. Orchards on the Sound shores did not suffer as much as did those farther back. In Seattle, ice six inches thick covered all of Lake Union and the snow lay on the ground for thirteen weeks. The mercury fell below zero several times.”

In his 1909 “History of Washington: The Rise and Progress of an American State,” Clinton A. Snowden wrote:

The ranchers and stock-growers in the Walla Walla country . . . the severity of the winter . . . turned their bright prospects of profit into an actual and almost ruinous loss. Most of their cattle perished. Many lost their horses also. Hay went up to $125 per ton, and flour to $25 per barrel. The loss of animals alone was estimated at $1,000,000, and many of the farmers were compelled to buy seed for the next year’s planting at ruinously high prices.

In 1906, the unidentified author of “An Illustrated History of Southeastern Washington” wrote: “The winter of 1861-62 was the severest ever experienced in the Asotin section of the country … this is the testimony of all the oldest Indians in the vicinity.”

All Over The Map: Wilkeson, Washington’s tragic Civil War namesake

W.D. Lyman wrote in 1918 in his “History of Old Walla Walla County, embracing Walla Walla, Columbia, Garfield and Asotin counties”:

This was the most terrible winter ever experienced in the valley. The snow drifted so deep that many of the cattle were frozen standing up. Out of 300 of ours, two cows and a calf, which we fed, were left. The timber wolves killed a good many cattle that winter. One day a wolf attacked a calf, and the mother heard the cry of distress coming from some distance. When she reached it, the wolf was starting to devour the body. The cow fought it from the calf for a day or two, making the most piteous cries. Other cattle smelled the blood and came bawling for miles around. The sound of hundreds of frenzied cattle bawling will not soon be forgotten.

There was a huge loss of livestock, especially east of the Cascades because of the cold and in Oregon and California because of the floods.

Schick says there’s no comprehensive list of human casualties for the winter of 1861-1862, but he estimates the number of people who died in Oregon, California, and Washington Territory could be as few as dozens or as many as hundreds.

From his research and from his experience as a scientist, Schick says that this winter season doesn’t appear to be part of any discernible larger or longer-range pattern.

“I think it was just a random event,” Schick said. “It’s not like the individual storms aren’t close to something we’ve already seen, [but] I think what’s unusual is this concentration in this eight-week period, especially the rain when it really starts to turn.”

Schick says that there’s one relatively recent weather event that reminds him of what he’s learned about the winter of 1861-1862.

“This is similar to what happened in a storm in 1996,” Schick said. That storm “got the southern part of the Puget Sound and then moved into Oregon [and] really hammered [them] . . . it was a similar type of storm – not quite as wet as 1861 – but nevertheless, a big, big modern storm,” Schick said.

One big difference between 1861 and 1996 is that there was “flood control going on, with dams holding back water in 1996,” he said.

Schick also says that he has searched archives around the region for photographs of storm damage in Washington and Oregon from the winter of 1861-1862 but that all he’s been able to find are images of extreme flooding in Sacramento and other parts of Northern California.

Maybe with all those weeks of subzero temperatures, it was just too cold to stand outside long enough to properly take a photograph with the slow cameras in use back then.

Editor’s Note:

This story was originally published on September 18, 2019.

You can hear Feliks every Wednesday and Friday morning on Seattle’s Morning News with Dave Ross and Colleen O’Brien, read more from him here, and subscribe to The Resident Historian Podcast here. If you have a story idea, please email Feliks here.